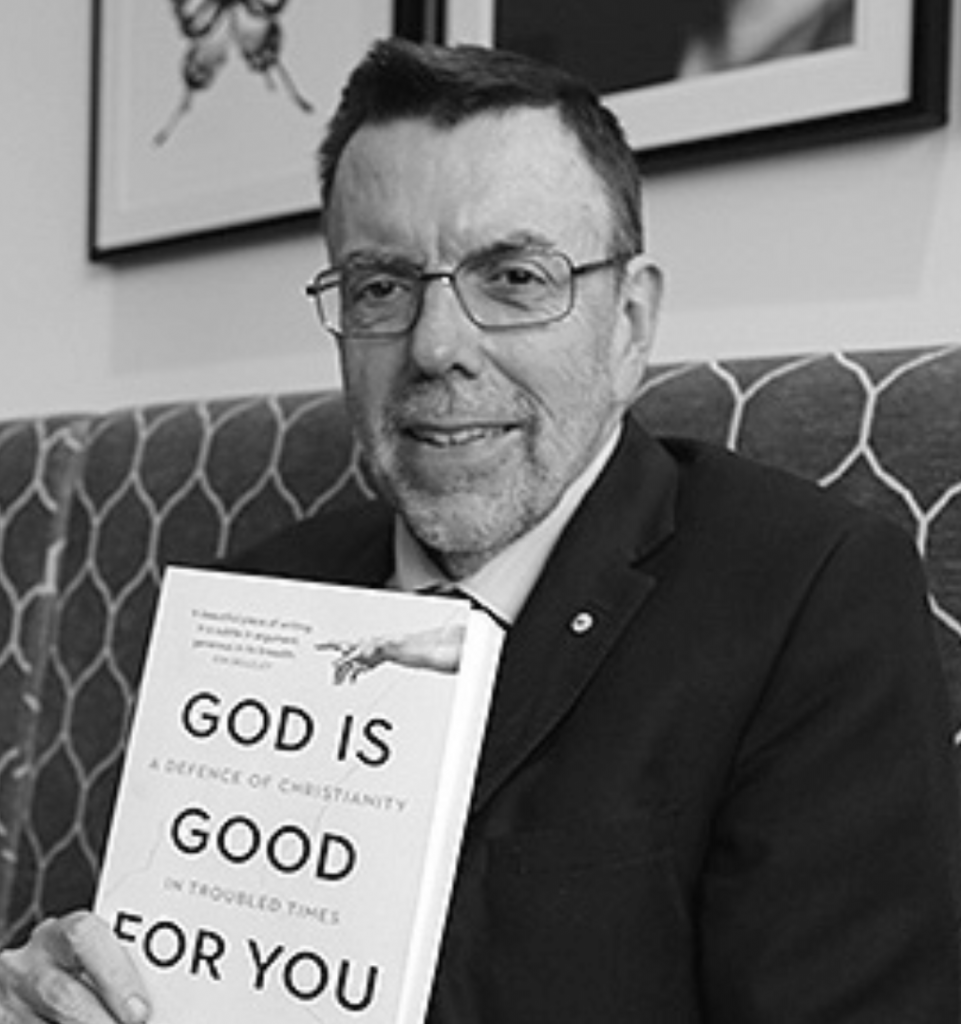

The admiration which the Foreign Editor of The Australian, Greg Sheridan, has for Chesterton is undisguised. He spoke at the 2016 Australian Chesterton conference on the inspiration Chesterton had given him as a journalist, and the previous issue of The Defendant (Summer 2020) published his photo (taken by his wife Jessie last year when he was a Visiting Fellow at King’s College, London) in front of Chesterton’s former London home.

Greg Sheridan’s reputation has widened in recent years as a result of his writings in defence of Christianity, in particular his best-selling book, God is Good for You. In this Weekend Australian article (Review section, February 7, 2020), reprinted with his kind permission, he applied a typical piece of Chesterton advice – frivolous on the outside, enlightening on the inside.

One of my great heroes in journalism and in life, G.K. Chesterton, had a sage piece of advice about how to look clever, advice he said he always followed himself. Whenever you are asked to write for, or speak to, a very serious audience, try to be funny. And whenever you are asked to write or speak to a normally light-hearted audience, try to be at least superficially profound, so to speak. You will surprise both audiences, who will think you very clever as a result.

Chesterton, the master of paradox, understood that much humour relies on two factors – introducing something unexpected, or introducing something familiar in an unexpected context.

Theological meaning in politics

Chris Uhlmann of Channel 9 makes occasional, quite deft use of his background as a seminarian studying to be a priest. I heard him talk once of analysing a prime ministership through the “via negativa”. This is a theological method of trying to know God only by knowing what God is not. Like Uhlmann, though less cleverly, I often introduce some elementary theological formulations in discussing politics, noting for example how rare the “angelic disposition” is in politics. The angelic disposition is the tendency of angels to do good purely for its own sake, rather than for the more human motive of avoiding punishment.

Catholic theological formulations can sound like voodoo if you’ve never been part of the tradition – the holy blood, the hypostatic union, holy mother church, the four last things (death, judgment, heaven, hell). These can illuminate a subject, but if you’re using them as humour their unfamiliarity means you have to explain them. But the best jokes often need a bit of explanation. Certainly they’re exotic.

They’re not so exotic, of course, to well-informed Christian audiences, so there I tend to use military terminology and metaphors. The churches need better situational awareness, or the centre of strategic gravity is moving, or the correlation of forces has changed. And Stalin’s great one-liner: in the argument between quantity and quality, quantity has a quality all its own.

Some Christian friends don’t like military metaphors being used in Christian contexts. Still, you can’t please everyone, especially with your metaphors. It’s embarrassing, though, to mis-use a metaphor in front of an audience that understands the subject too well. So I avoid military metaphors with military audiences.

In that case I’m more inclined to use elementary financial terms, such as declaring myself to be like a stock analyst contrarian, taking a position against the consensus of analysts. Or I might talk of describing China’s geo-strategic power as a chartist analyses a stock, understanding its various ups and downs, but trying to chart those short- term stock movements within a broader net band moving either upwards or downwards.

Naturally therefore when talking to a finance audience I use international relations jargon: talking of soft power, international norms, the rules-based order, etc. I’m a pretty hard fellow to embarrass, but there is almost no jargon known that is more nakedly designed to add the appearance of substance to pure wind, as Orwell put it, as international relations jargon. Its use does sometimes bring a blush even to my generally unblushing cheeks.

None of this jargon switching is rocket science, but it is an essential part of the giant game of bluff involved whenever you are so bold as to make a big statement on a big subject. Suggesting, though of course never quite claiming, a world of expertise through the use of exotic jargon disguises the one true thing you can say about the future – it’s unpredictable.