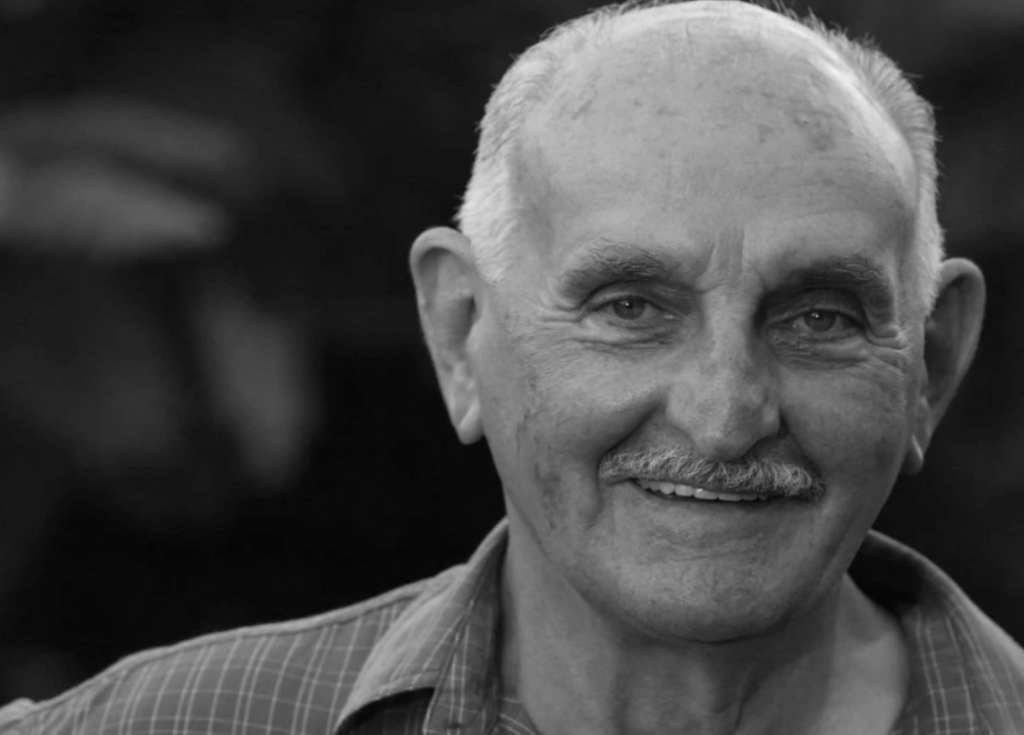

It is improbable that Chesterton and the Australian poet, Bruce Dawe (pictured), were known to each other, as Dawe was only 6 years old when Chesterton died in 1936. But they would have found much in common if they had been part of the same generation.

Dawe died in Queensland on 1st April at the age of 90. He had a prolific output and his poems were commonly included in high school and university curricula. He published more than 10 books of poetry, and his signature collection, Sometimes Gladness, which he dedicated to St Maximilian Kolbe, went through six editions between 1978 and 2006 as newer poems were included on each occasion.

But the pivotal reason for his popularity would have resonated deeply with Chesterton. He had an extraordinary empathy with ordinary people, and showed how poetry could give imaginative expression to their lives.

Dawe was born in Melbourne in 1930, the youngest of four children. His parents were from a farming background, and their move to the city led to much shifting around. By the age of 16, Dawe had attended 10 schools – an experience he evoked in one of his best-known poems, “Drifters”.

The family had limited educational opportunities: Dawe was the first to study beyond primary school. While he later completed four university degrees – including a doctorate on the English war poets – and was appointed to lecture in English literature at the University of Southern Queensland in Toowoomba, he never abandoned his cultural roots.

The poetic imagination in Australia has long contended with a deeply secularist culture closed to transcendental meanings. Dawe was a vital example of a counter-tradition represented by Catholic converts – poets such as James McAuley, Les Murray and Kevin Hart.

Like McAuley, Dawe’s conversion took place in the 1950’s. He was in his early 20’s, seeking purpose and direction in life. He studied initially at the University of Melbourne, which brought him into contact with Catholics, in particular Vincent Buckley and other Catholic poets, which nurtured his interest not only in Christianity but also imaginative writing.

For Dawe, the special attraction of the Catholic Church was the richness of its ritual and the luminous lives of the saints. His interest in ritual was inspired by the beauty of High Church Anglican services. Just as Chesterton was indebted to his wife, Frances, for the inspiration of her deep Anglican faith, so Dawe gratefully acknowledged the influence of a high school teacher who combined her vocation as a Methodist lay preacher with Sunday morning participation in Anglo-Catholic services.

In his poetry Dawe caught the connections between his Christian faith and the experiences of ordinary life. He captured in everyday language our human yearnings and

devotions, our fears and frustrations, our sufferings and grievances. Unlike Chesterton, he had a passionate love of football (Australian Rules), which he celebrated in a number of poems, notably “Life Cycle”, dedicated to ex-Collingwood committee man Big Jim Phelan.

Dawe was ever conscious that his faith gave a new centre of meaning and higher purpose to all these experiences. “We have to preserve a vision,” he said. “Writing is part of a total moral vision. You just can’t escape that.”

A crucial part of this moral vision was his opposition to abortion. His powerful poem, “The Wholly Innocent,” in which he protests against the destruction of the unborn by imagining himself as one of the vulnerable, bears comparison with Chesterton’s poem, “By the Babe Unborn”, in which the unborn child longs to be born. (Dawe’s poem is excerpted first, followed by Chesterton’s.)

I never walked abroad in air I never saw the sky Nor knew the sovereign touch of care Nor looked into an eye. . . . Remember me next time you Rejoice at sun or star I would have loved to see them too I never got that far.

In dark I lie; dreaming that there Are great eyes cold or kind,

And twisted streets and silent doors, And living men behind. . . .

I think that if they gave me leave Within the world to stand,

I would be good through all the day

I spent in fairyland.

They should not hear a word from me Of selfishness or scorn,

If only I could find the door,

If only I were born.

Bruce Dawe was steeped in the experience of ordinary Australian life – and only Australia could have produced him. But his faith raised this experience to a higher plane, and offered a Chestertonian reminder of the light which transcendent truth can confer on temporal reality.