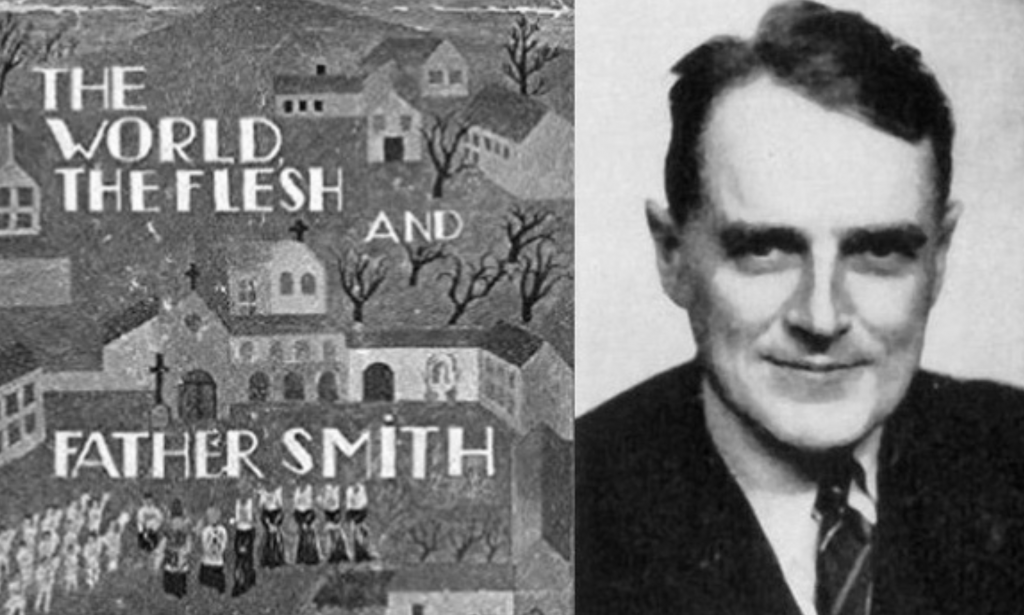

Bruce Marshall (1899-1987) was a Scottish Catholic writer who became best known for a series of novels with religious themes, beginning with Father Malachy’s Miracle (1931). Two of his novels were translated to the screen – Vespers in Vienna (1947), which came out as The Red Danube in 1949 and starred Walter Pidgeon and Ethel Barrymore, and The Fair Bride (1953), which was the basis of the 1960 movie, The Angel Wore Red, starring Ava Gardner and Dirk Bogarde.

Another Marshall novel, The World, The Flesh, and Father Smith, has been reprinted (2017; orig. ed. 1944), and Gary Furnell offers a fresh introduction to a neglected Catholic author. Gary, who is secretary/treasurer of the Australian Chesterton Society, contributes articles and book reviews to various journals and newspapers, including the Sydney Catholic Weekly, where a shorter version of this review first appeared.

In order to properly review this book, I read it twice in two months. I had not heard of Bruce Marshall, nor previously read such overtly Catholic fiction; I was pleased to discover that this novel is both good literature and entertaining.

The chapters are short, the characters are sharply delineated, and the narrative is spiced with shrewd observations, frequent wit and occasional farce.

The writing from start to finish is accessible, engaging, well-paced and sometimes strangely poetic; for instance, observing the short skirts of two young women, Father Smith, the main character, says they dress as if their wobbly bottoms are “wiser than Aristotle”. That phrase will come to mind next time I go to the beach.

On another occasion, at the Carlton-Elite Hotel, Father Smith watches the rich sophisticates “smoking with aggressive venom as though they were doing something both sinful and complicated, like committing adultery in Russian.”

When Father Smith is introduced, he is fifteen years into his priesthood, serving in a working-class section of a Scottish town where Catholics and their Popish ways are viewed with suspicion and sometimes with open hostility. We are told briefly how Father Smith came to his vocation as a young man, but his childhood and youth are largely skipped, taking us straight into his mature priesthood. His life is joined to his clerical colleagues and a small band of exiled French nuns. We follow these characters from the period prior to World War I to Father Smith’s death in the early 1940s.

These four decades coincide with the rise of Modernism which was, as Chesterton wrote, not a new idea or the development of an idea but the abandonment of an idea: the idea of Western Christendom.

In an early chapter Father Smith and two other priests visit the new technology of a moving picture house — owned by one of the parishioners — and they worry about the effect of this diversion on their parish. Expecting sin and folly, they all hugely enjoy a Western and a slapstick cops and robbers reel. Over the years the various movie genres and their stars come and go in quick succession. The cinema-owner’s daughter, baptized by Father Smith, becomes a Hollywood actress and struggles to reconcile her fame with her faith. The cinema owner, an Italian man, is enamored of Mussolini and believes the Duce’s pronouncements of restored greatness for Italy.

Changing fashions, unchanging promises

As he moves about town, Father Smith notes the passing parade of cinema and literary fashions, advertisements, women’s clothes and attitudes, and the false promises of politicians and opinion-makers. The contrast between the eternal teaching of the Church with the merry-go- round of worldly pleasures and ambitions is evident but left for the reader to mark. Catholics in an increasingly anchorless, secular society is a theme in the novel.

War and its aftermath is another obvious theme. Father Smith enlists, in his late thirties, as padre in World War I. He serves on the Western Front, sees the suffering, comforts the fearful and dying, and hears the hopes that the war will bring a better world.

Even the bishop and his fellow priests expect a rebirth of spirit and civilisation after all the horror and the lives sacrificed. Of course, the opposite happens as hedonism, restlessness, joblessness and other indignities prevail.

De-mobbed, Father Smith returns to parish work. Over the years, the small tin shed that long-sufficed as a chapel is replaced by a handsome stone church; the French nuns establish a school; babies are baptised, marriages and funerals solemnised and pastoral work undertaken in poor, damaged families.

The Catholic community becomes ensconced in the town. There are even some converts, although too many cradle Catholics and Protestants fall into unbelief or, rather, into faddish beliefs. In an amusing encounter, Father Smith is taken to task for his oppressive religion and repressive celibacy by a young, opinionated, free-loving Communist woman. His courtesy tested and really angry, Father Smith says to her “You do talk a lot of balderdash, don’t you?”, and he wishes that “his holy religion did not forbid him to slap the young woman’s face.” Instead, he responds to her ephemeral fancies with facts and the sapience of faith. He reflects later that celibacy becomes ever more attractive as he meets more women like her.

To arrest their community’s slide into fashionable unbelief and lassitude the priests organize a mission and get the fiery Monsignor O’Duffy to preach. The mission fails. Chastened by their lack of success, the priests learn again the value of trust in the mystery of God and in the traditional patient ways of the Church.

The novel closes with a series of deaths: the Bishop, Mothers Leclerc and de la Tour, Father Smith’s priestly colleagues, and finally Father Smith himself are buried. A new generation of religious men and women take their place. A lot happens in only 223 pages.

The prophetic voice

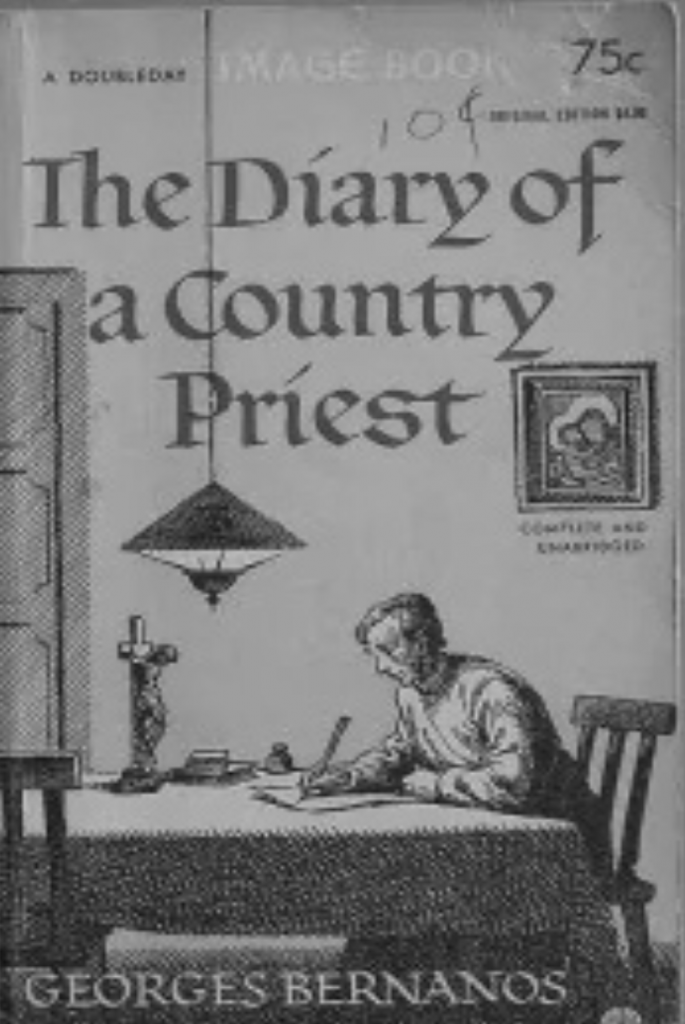

One quality of this book, and I noted the same quality in George Bernanos’s novel, Diary of a Country Priest, is the prophetic voice. In both books the main characters are pious men (although in very different circumstances) who see with spiritual eyes. They lament the destructive irreverence, greed and selfishness of their culture.

The expression of their

trascendent clarity and wisdom

is not an imposition on the stories but part of the rich texture because of the protagonists’ vocation, and it comes with the ready admission of their own troubles and inadequacies. It’s no surprise that this prophetic but broken voice is missing in the great majority of novels because temporal concerns are often the only concerns.

This prophetic voice is ultimately Bruce Marshall’s voice. A Scotsman, Marshall was a Protestant who converted to Catholicism, an accountant who wrote novels. He said that among accountants he is thought to be a significant novelist, among novelists he is assumed to be a competent accountant.

He served in the Royal Irish Fusiliers in World War I. One week before the Armistice, he was badly wounded in the leg. Brave German stretcher-bearers ventured into no man’s land to rescue him—they saved his life, but he lost his leg.

After the war, he married, settled in France and wrote novels and audited ledgers. He took his family back to England as the Nazis rolled over Europe, and served in the pay corps and then intelligence services in World War II. After the war, he returned to France and devoted himself to writing.

He wrote forty books, many well-received and some quite popular. Despite this success, his work has suffered neglect until this welcome re-issuing of The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith. Other titles are expected to surface in new editions.

Chesterton thought it was easy to make calamity more interesting than goodness because goodness was normal and undramatic whereas calamity was rare and therefore dramatic. In The World, The Flesh and Father Smith, Bruce Marshall succeeds in the difficult task of making common goodness interesting as he portrays a devout man who is secure in his faith and glad in his role.

Flannery O’Connor thought that, however we defined a novel, it had to be wide enough to include her own odd novels. It also has to be wide enough to accommodate unfashionable novels about orthodox priests and their everyday activities.

The World, the Flesh and Father Smith is not a work of “holy bilge and sacred bunk” as Father Smith himself describes some Catholic writing, but of careful artistry that creates worthwhile fiction.