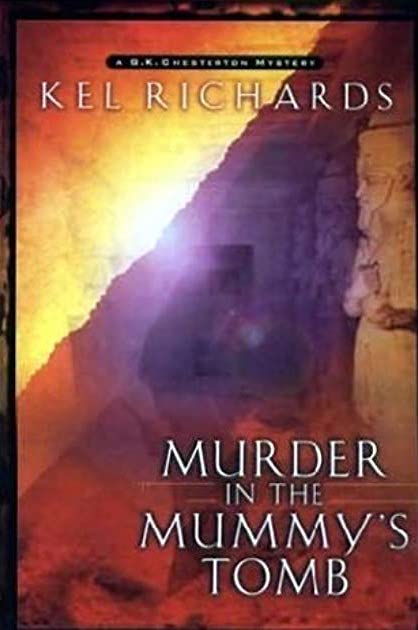

Kel Richards is a well-known Australian broadcaster and wordsmith who also writes crime novels. His novel, Murder in the Mummy’s Tomb (2002), features Chesterton as one of the fictional characters. John Young, who has written previously for The Defendant on Chesterton’s detective fiction, reviews Kel Richards’ novel.

This is a locked room mystery, or rather a locked tomb mystery, and the author has included two real people among his fictional characters: Gilbert and Frances Chesterton.

Set in 1919, an archaeological team opens an ancient Egyptian tomb and finds it has two occupants: the ancient Egyptian they had expected to find and a freshly murdered member of their own team.

Against this central mystery the author sketches the contrasting characters, their relationships and the tensions between them. A romantic relationship develops between the young archaeologist who tells the story and the daughter of the expedition leader.

But not all the characters are fictional. G.K Chesterton and his wife Frances arrive on the scene, and after the murder is discovered he sets himself to solve the mystery. An interesting aspect of the novel is the way Kel Richards portrays Chesterton’s character in conversation with the fictional characters of the story.

His boisterous nature is evident, his quick intellect, key elements of his philosophy. His dialogue, when it touches the deeper issues of life, often repeats statements found in his books and essays. His philosophy of life is shown in contrast with the various views of the other characters.

To a character who regards theology as irrational Chesterton replies: “your mistake, young sir, is to assume that theology is irrational. It is not. It is the rational mind at its finest. A man is never thinking more logically than when he is thinking theologically.”

To another character, who thinks Christianity is the thinking of yesterday, Chesterton replies: “I should certainly hope it is the thinking of yesterday, which is what makes it true today. Otherwise, you might as well say that a philosophy can be believed on Mondays but not on Tuesdays.”

In another conversation Chesterton recommends the book St Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen by Sir William Ramsey, which shows “how accurate and reliable the New Testament is”.

Chesterton had a great deal of illness during his life, and his ill-health is emphasised in this novel. His weight is often mentioned, he is described as having three chins, he is often short of breath and clearly out of condition. But his intellect is strong and clear.

He investigates the perplexing mystery. The tomb in which the murdered man was found had clearly not been disturbed since the ancient Egyptian had been buried. There was no way in until the archaeologists broke their way in. Yet when they entered they found the murdered member of their expedition.

Kel Richards plays fair with the reader (Monsignor Ronald Knox would have approved), and if the armchair detective can’t solve the mystery he should not blame the author.

Although published in 2002 this novel has the tone of earlier detective stories. There is no sex, there is no bad language. There is a wholesomeness about it in contrast with so much recent fiction.

I can’t judge the accuracy of the archaeological and Egyptological information scattered through the book, but the author acknowledges the help with these matters given to him by Dr Karen Sowada, so I presume it is accurate.

The story moves along at a good pace with a cast of twenty- two characters, including journalists, two clergyman, a British Army Intelligence officer and an escaped convict. The author has thoughtfully provided us with a list of the characters.

It is an interesting story, the clues are given fairly, while Chesterton’s personality and his philosophy are well presented.