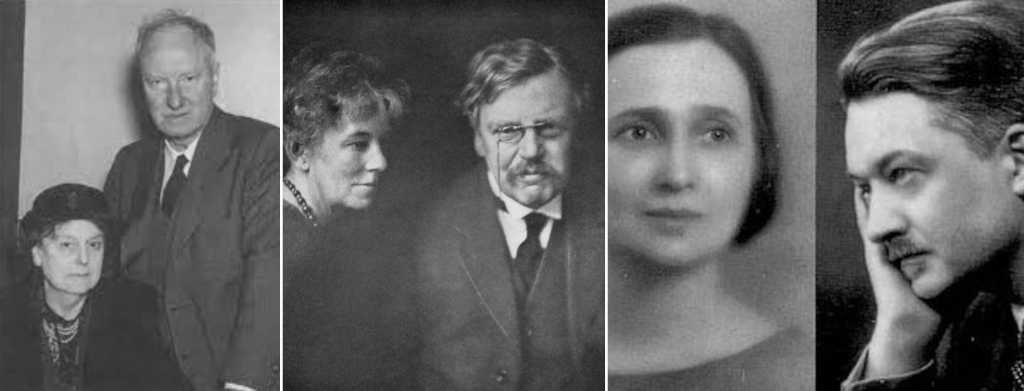

The Melbourne-based philosopher, John Young, highlights the crucial influence of three women in the lives of their better known husbands.

A number of eminent Catholic authors might have remained unknown were it not for the influence and support of their wives. Jacques Maritain, Frank Sheed and Chesterton are examples.

Jacques and Raïssa

Maritain met Raïssa Oumansoff when they were undergraduates at the Sorbonne in Paris, both searching for a worthwhile philosophy of life at the beginning of the 20th century, and appalled at the hopeless materialism surrounding them, yet which they feared was the best that life could offer. They contemplated suicide unless they could find a philosophy worth living for.

It was through their mutual support that they succeeded, first through discovering Catholic spirituality and then the richness of Catholic philosophy. But it was Raissa who first read St Thomas’s Summa and then introduced her husband to that great work. He was to become one of the very best philosophers of the 20th century.

In her Adventures in Grace Raïssa describes her first reading of St Thomas’ Summa: “So great a light kept flowing into both my heart and mind that I was carried away as if by a joy of Paradise”.

After Raïssa and her sister Vera had died, Jacques said: “I have lived with two saints”. Raïssa had been his great support.

Frank and Maisie

Frank Sheed took a break from his study of law at Sydney University to go overseas, and in England joined the Catholic Evidence Guild and fell in love with one of its leading members, Maisie Ward. They founded the very influential Catholic publishing firm of Sheed and Ward, and Sheed became an outstanding exponent of the Catholic Faith.

Had it not been for Maisie he would probably have returned to Sydney and eventually have become a leading barrister.

Gilbert and Francis

What would Chesterton have become had he never met Frances Blogg? Of course we don’t know, but the outcome may well have been disappointing, or even disastrous. He dedicates his great poem The Ballad of the White Horse to Frances, and the dedication includes the words “You who brought the Cross to me”.

Certainly he had massive common sense, but he also lived in the midst of conflicting philosophies, even dabbling for a short period in occultism. He gave that up after fearing that he was playing with fire, “and even with hellfire”.

He must have been profoundly influenced by Christianity as he saw it in the life and beliefs of Frances, helping him to the deep insights found in his brilliant work Orthodoxy, published 14 years before he became a Catholic. Frances was a devout Anglo-Catholic.

Apart from her influence on his religious beliefs he needed her to bring some sort of order into his absent-minded life. As on the occasion when Frances was ill and probably not well enough to supervise him, he called at a neighbour’s place on his way to a meeting, and was wearing a shoe on one foot and a slipper on the other!

In their student days Jacques and Raissa had resolved to commit suicide if they were unable to find any meaning in life. Many years later, after Raissa had died, Jacques returned to the site of that resolution, and it was there that the last photograph of him was taken.

Soon after Maisie died I happened to meet Frank Sheed in Sydney, and when he spoke about her it was as though she was still present to him.

In her biography of Frances, The Woman Who Was Chesterton, Nancy Carpentier Brown comments that “few voices remained to speak of the woman behind the man who was Chesterton”, and she quotes from one of those few: Father John O’Connor (the priest on whom Chesterton’s Father Brown was based).

Father O’Connor wrote to Frances, after Gilbert had died, that none of the death notices tells the secret “of how much of him and his best might have been lost to the world only for you.”