The vastness of Chesterton’s mind found expression in a vast output, and the challenge of capturing it in a bibliography would daunt even the most ambitious scholar.

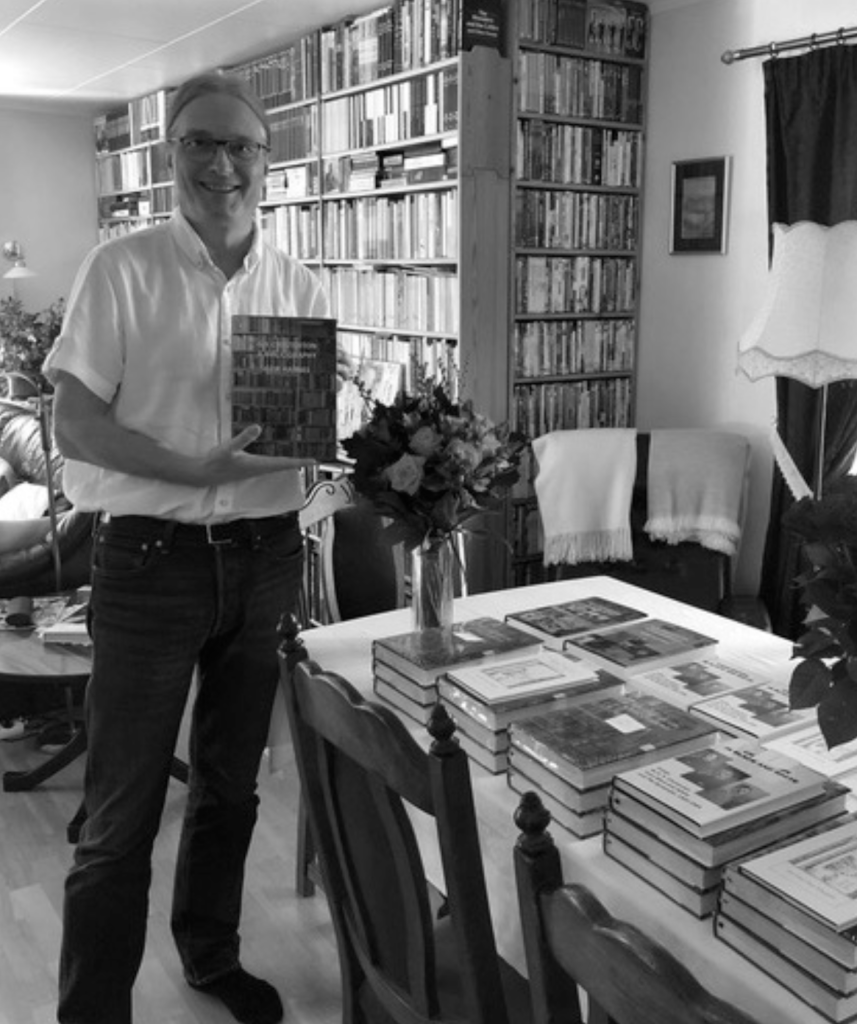

Geir Hasnes is a Norwegian researcher who refused to be daunted. His long-awaited bibliography, G.K. Chesterton: A Bibliography, has now been published in three hardbound volumes.

It more than fulfils expectations as a truly phenomenal achievement – a work of comprehensive coverage and scholarly value which could not be surpassed.

The bibliography contains the expected listing of Chesterton’s books and pamphlets (with abundant detail of their contents and publication history), as well as of his contributions to well-known periodicals such as the Daily News, the Illustrated London News, and G.K.’s Weekly.

But it has also managed to gather in a huge number of articles that were published in hidden and elusive places.

One example is the Chesterton pieces published in Australia, usually from British periodicals, such as in the Catholic Fireside (a monthly magazine founded in Sydney in 1934) and Freeman’s Journal (now the Sydney Catholic Weekly).

A special section on “Australian Sources” notes a remarkable range of newspapers and journals that reprinted Chesterton’s articles and gave lengthy accounts of his speeches.

Volume I and the first half of Volume II of the bibliography itemise these works in clear and painstaking detail. They reflect Geir Hasnes’ operating principle of having a copy of everything at hand for examination, to ensure he could check content and sources directly and personally.

The remainder of Volume II records works by other authors relevant to Chesterton. One category of special interest is the works that feature his illustrations (as the natural artist he was throughout his life), particularly in the novels of Hilaire Belloc.

Another part of Volume II is an extensive section, of over 500 items, which lists books and pamphlets written on Chesterton, ranging from major biographies and specialised studies to works partly devoted to his thought and writings. It conveys a remarkable picture of the enduring and worldwide interest he has generated for more than a century.

Volume III is in some ways the most fascinating compilation as it covers the most varied material – for example:

- periodicals devoted to Chesterton (including our own Australian quarterly, The Defendant, listing authors and articles);

- portraits and caricatures of Chesterton;

- translations of his works in many languages (amounting to over 1,300 items), representing not only European countries and (in Spanish and Portuguese) South America, but also Asia (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Thai) and the Middle East (Hebrew);

- films based on Chesterton’s works – the most recent entry being the Australian-made movie of his play, Magic;

- significant Chesterton collections in mainly university libraries in the UK, Canada and the USA;

- impersonations of Chesterton as a character in fiction, including in Kel Richards’ Murder in the Mummy’s Tomb: A G.K. Chesterton Mystery (2002), and parodies of his style in over 50 books and a great many short stories, particularly relating to Father Brown.

The English poet and editor, Sir John Squire, once remarked of Hilaire Belloc, that “the man who attempts to survey [his] writings will think he is undertaking to write the literary history of a small nation.”

Belloc was prolific, but this vast bibliography suggests that Chesterton was more like a large nation!