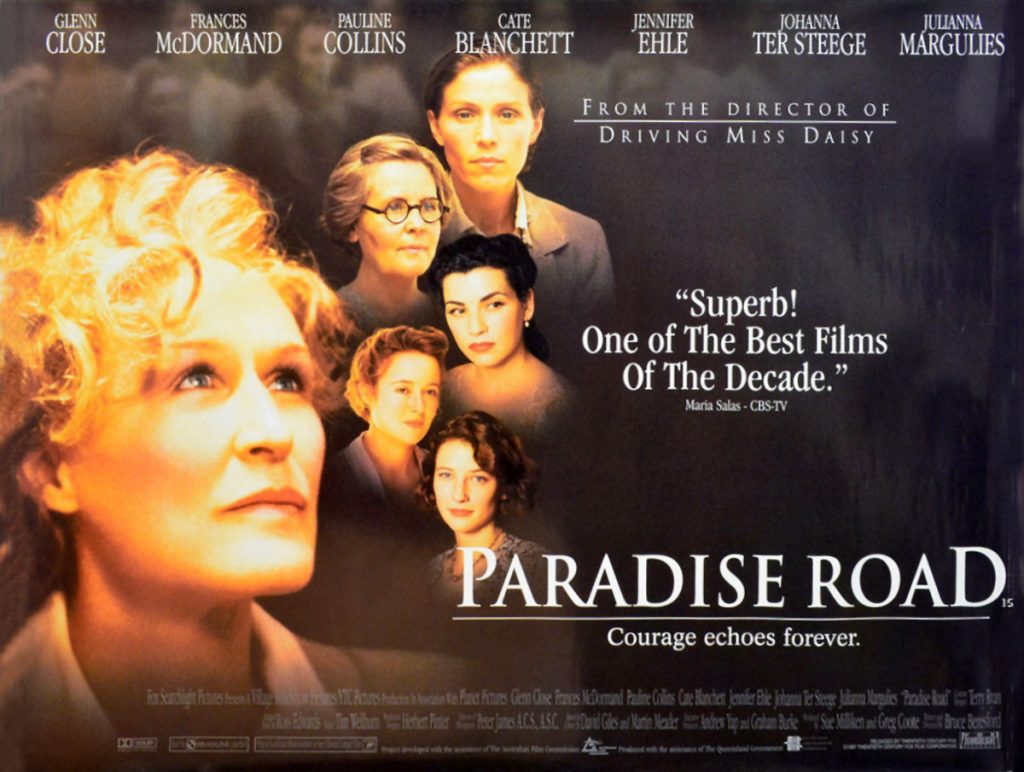

In his online newsletter on November 15, 2022, David Daintree, Director of the Christopher Dawson Centre for Cultural Studies in Hobart, reflected on the merits of the Australian movie, Paradise Road. His review is reprinted here with his kind permission.

I recently watched the 1997 Bruce Beresford film Paradise Road at home on DVD. As the standard of free-to-air TV continues to plummet gutterwards, I find the urge to fossick through our old disc collections grows all the stronger!

Paradise Road is a triumph of the Australian film industry. It focuses on the horrors of prison life in Sumatra under Japanese occupation during the Second World War, but without confining its attention narrowly to the Australian victims only: one of the leads is our own Cate Blanchett, but other main roles are taken by Glenn Close (American) and Pauline Collins (English).

I think it’s one of the characteristics of good Australian movies (and Beresford’s are up there with the very best) that they are patriotic without being nationalistic: we are right to be proud of our people bravely enduring the most appalling sufferings, but we’re citizens of the world and so must equally recognise greatness in others.

Glenn Close’s performance wins the palm in my view. She plays the part of the real-life Norah Chambers, a professional musician who established a sort of choral orchestra in the camp.

The prisoners are forbidden to have musical instruments, but under her direction they hum their music, raise their own spirits – and occasionally even entrance their guards.

Close’s performance is an awesome and incomparable piece of acting, I think, but the co-founder of the orchestra, the missionary Margaret Dryburgh (played by Pauline Collins), won my heart. She wrote a poem called The Captives’ Hymn which is featured in the film, most movingly at the funeral of one of that majority of poor POWs who lost their lives through sickness and ill treatment. Here are a few lines:

“Father, in captivity,

We would lift our prayers to Thee, Keep us ever in Thy love,

Grant that daily we may prove Those who place their trust in Thee More than conquerors may be.

“May the day of freedom dawn, Peace and justice be reborn,

Grant that nations loving Thee

O’er the world may brothers be, Cleansed by suffering, know rebirth, See Thy kingdom come on earth.”

It is impossible for those of us living in Australia today to come close to imagining the privations endured by prisoners of a cruel regime, during a war that must have seemed never-ending, not knowing if lost loved ones were alive or dead. They must have hated their captors for their pitiless cruelty, yet so many of them probed beyond hatred to sympathy and eventually love: “grant that nations loving Thee o’er the world may brothers be.”

This is such a generous movie. It doesn’t leave us hating the Japanese, though so many of the things they did to the most vulnerable people were indeed hateful.

Instead, Beresford allows us a glimpse of the humanity of the defeated enemy: the rare smile between soldier and prisoner; the occasional look of shame in the eyes of men implicated in horrible things; their final disgrace in the face of defeat.

We know that Japan treated its soldiers cruelly too. Theirs was a world where few knew the Gospel, where might alone conferred rights.