Reflections of an undertaker’s assistant

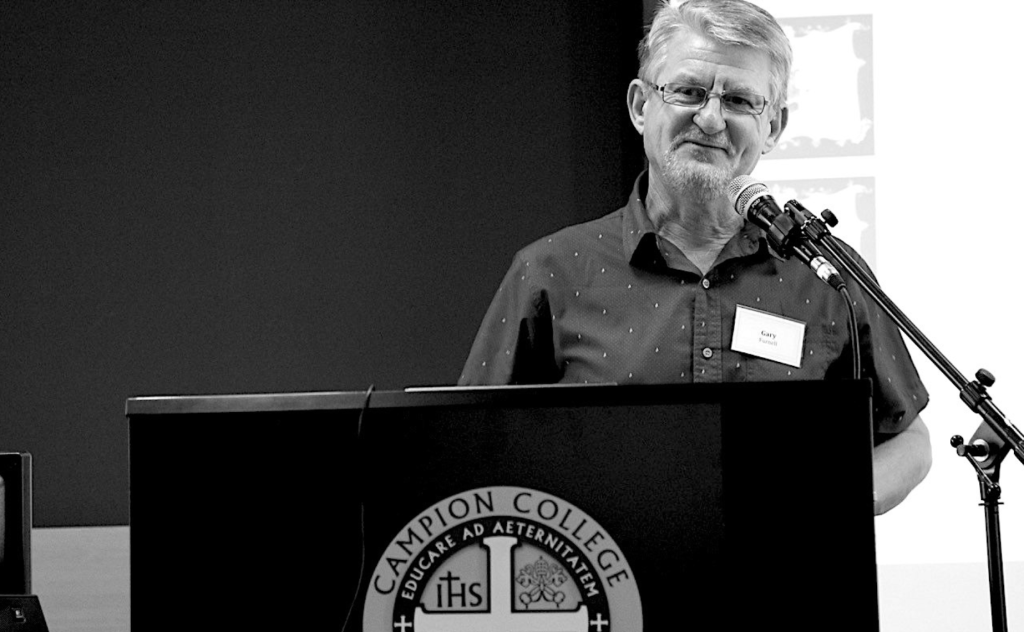

In his recent work as an undertaker’s assistant, Gary Furnell (pictured) has observed the cultural and religious changes that are reflected in funeral customs in Australia. Gary is a frequently published contributor to Quadrant, News Weekly and other journals, as well as serving as the Australian Chesterton Society’s Secretary-Treasurer.

Prayers and Poems

Changes in our society — in particular, secularisation — are reflected in funeral customs.

For example, only a generation or two ago in Australia, nearly everyone knew the Lord’s Prayer even if they never went to church. It was part of our culture. Not anymore. The Lord’s Prayer is still included in many funerals but, if it isn’t

written in the order of service, most people can’t recite it.

When I assist at funerals, I often notice younger mourners glancing with wonder at older mourners who can say the prayer from memory. That memory was never given to those young people, and they’re poorer for its absence,

disconnected in one more way from their cultural heritage.

In contrast, the heritage of rhyming verse stubbornly persists at funerals. Poems, always with pulse and rhyme, are often featured during services. Unrhymed, unmetered verse is seldom heard. This may disappoint the modernists, but when people want solemnity — to honour the dead and the deeply loved — they instinctively choose poems with rhyme and rhythm.

The poetry may not be great (more often it’s close to doggerel), but it satisfies a real need which free verse doesn’t satisfy. Lovers and mourners share this preference for traditional forms of poetry, possibly because those who

mourn and those who love are the same people.

The poems at funerals are an attempt to capture — in some way — the mystery of another person’s life.

Eulogies are likewise an attempt to capture the mystery of a life. The focus is frequently on obvious aspects: the deceased loved their garden, their family, their mates, their footy side, their fishing or holidays. But the complex inner life of another person is largely closed to anyone except that particular person. This is true of us all. We’re a mystery to other people because we’re mostly a mystery to ourselves.

Family, Friends, Home

What eulogies consistently reveal is that, overwhelmingly, most lives very sensibly revolve around family, friends and home.

We may love a sport, our bank account, hobby, club, political affiliation or our work, but it’s our family and friends that we particularly cherish. And we are most ourselves at home with our loved ones; at home we have the greatest freedom to express ourselves. Women — very generally speaking, family builders — seem to possess the good sense to value intimate blood relationships more overtly than men. But the wise predilection to treasure close relationships — above everything else — is common.

It’s also common that people build relationships with unequal skills. At a funeral it’s a delight to see family and friends pleased to see each other as they gather to mourn. Little cousins cheerfully greet each other; kisses and lasting hugs are exchanged among adults; grief is expressed and then consoled with sincere solicitude. Tenderness is shown to the elderly and those deeply bereaved. Functional families dress with appropriate care showing they understand the importance of a dignified occasion.

Dysfunctional families are not a delight. Men dress slovenly as if they’ve rushed to the funeral from working under the car, from the pub, or the beach. They walk in and out of the funeral to have a smoke. Too many young women seem to think the clothes fit for night-clubbing are the right clothes for a funeral.

Unfortunately, funeral directors may be required to separate families because they’re quarrelling and can’t contain their ill will. Eulogies can become an occasion for vulgarities and tension rather than consolation and

celebration.

For some, honouring the dead appears a trivial matter: they arrive at a funeral with a takeaway coffee or a Red Bull to slurp during proceedings.

There’s a widespread lack of knowledge about good funeral customs. I’ll be teaching my children those good customs, particularly if they plan to come to my funeral. At that time I hope the coroner — finding remnants of a chocolate

éclair and cappuccino in my belly — will have concluded: “He died happy.”