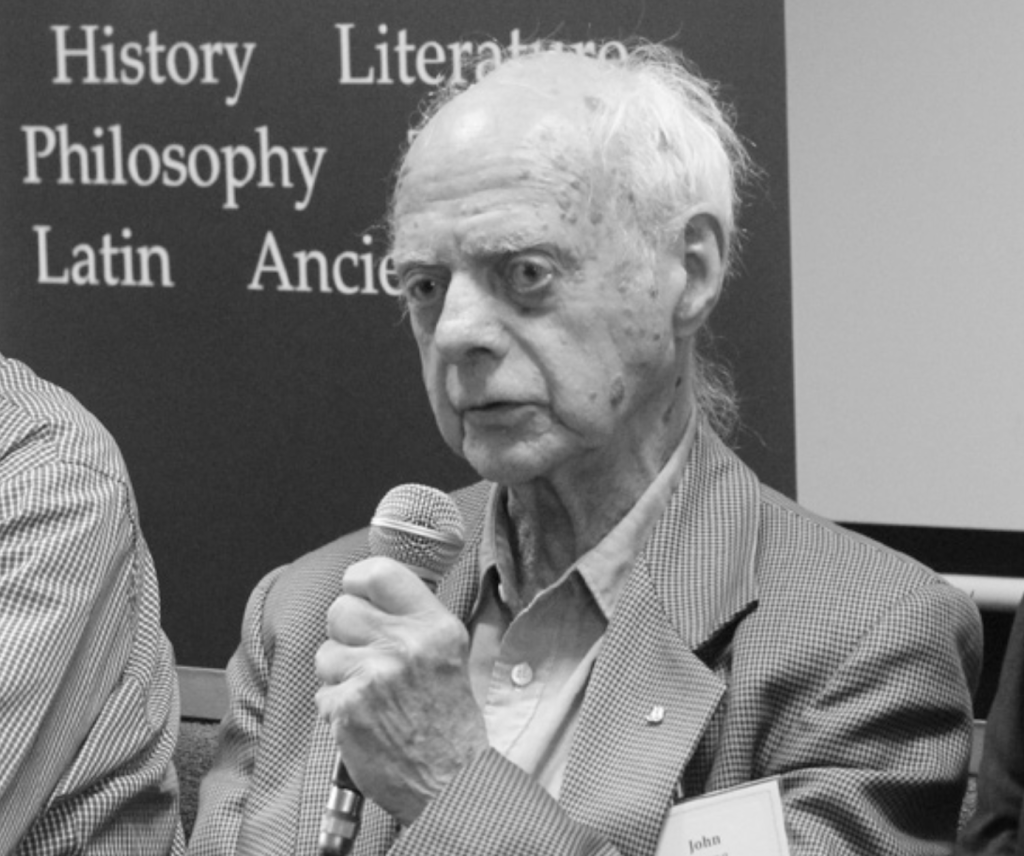

Has the flight from reason now turned into a revolt? John Young, a Melbourne-based philosopher and frequent contributor to The Defendant, reflects on the present nature of irrationality in our culture.

Chesterton claimed, in 1925, that most freethinkers who attack Rome by an appeal to reason are falling from Reason even more than from Rome (Introduction to God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy, by Fulton J. Sheen).

The abandonment of reason by so-called freethinkers has accelerated in recent years, and with it an abandonment of nature and denial of any natural order. There is even a difficulty now about answering the question: What is a

woman?

I don’t think Chesterton would have been surprised at the development of irrationality that we encounter today. He may have wondered if the flight from reason had now turned into a revolt.

In the story The Blue Cross, the criminal Flambeau, disguised as a priest, betrayed himself when he denied reason. He suggested that there may be wonderful universes in which reason is utterly unreasonable.

Attacking reason is bad theology

When he asked Father Brown how he knew that Flambeau was not a priest, Father Brown replied: “You attacked reason. It’s bad theology”.

Today also (hopefully) a pseudo-priest would be detected if he made that error, but probably a pseudo-philosopher would not be detected when he attacked reason.

Philosophy deals with the deepest questions, so far as reason can know them. But this implies that mistakes in those sublime matters can be more radical and more devastating than errors in less profound questions.

Today’s fall from reason is often also a fall from science and from common sense, as in puzzlement as to what a woman is.

The 13th century is still assumed by many to have been part of the alleged Dark Ages that followed the fall of the Roman Empire, a time when theologians busied themselves with discussing how many angels could stand on the head of a pin. (Incidentally, when Sir Arnold Lunn researched this alleged question, he could find no trace of it among the mediaeval theologians. But he pointed out that it could be a useful illustration in considering the relation of a spiritual being to space.)

In reality, the 13th century was a time of outstanding intellectual activity in the universities, with questions thoroughly debated. It was then that the world’s greatest work of theology, the Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas, was written. In every article St Thomas first poses objections to his own position and finishes the article by answering those objections. There are, according to the people who count these things, some 10,000 objections dealt with by St Thomas in the Summa.

A theme in Chesterton’s Father Brown stories is the assumption by prejudiced people that this Catholic priest is not rational, due to his (allegedly) irrational religious beliefs. Then it turns out that his critics are the irrational ones. He is assumed to be superstitious, but it turns out that his critics are the superstitious ones.

For example, in The Oracle of the Dog people misinterpreted the behaviour of the dog because they were implicitly asking themselves: “What does the dog’s behaviour mean if the dog is an oracle?” Father Brown asked himself (although not in these words): “What does the dog’s behaviour mean if the dog is a dog?”

Natural laws replaced by arbitrary laws

Today there is a dictatorship of relativism, with irrational positive laws replacing natural laws. Of course there must be positive laws: that is, laws that derive their validity from the authority of the lawgiver; for example, a traffic law that vehicles must keep to the left. But valid laws of this kind get their validity from underlying natural laws, such as the obligation to value human life.

With the denial of natural laws we get arbitrary positive laws based often on irrational feelings or prejudices. As Chesterton stated:

If we break the big laws we don’t get freedom and we don’t even get anarchy. We get the small laws.

The Man Who Was Orthodox, 1963