A notable phenomenon of our times is the proneness to exaggeration.

The conversations of our culture, especially in politics and current affairs, fall easily into the use of superlatives. “Excellent” or “disastrous”, “greatest ever” or “worst ever”, slip easily off the tongue.

“Outstanding” has now become such a common term of praise that anything less might be construed as lukewarm – and almost an implicit criticism. “Catastrophic” immediately lifts an event from the exceptional to the unprecedented.

The instinctive resort to exaggeration no doubt reflects the marketing dynamics of our culture. Excessive language excites attention – and promotes the selling of products; but it is now serving a much broader role.

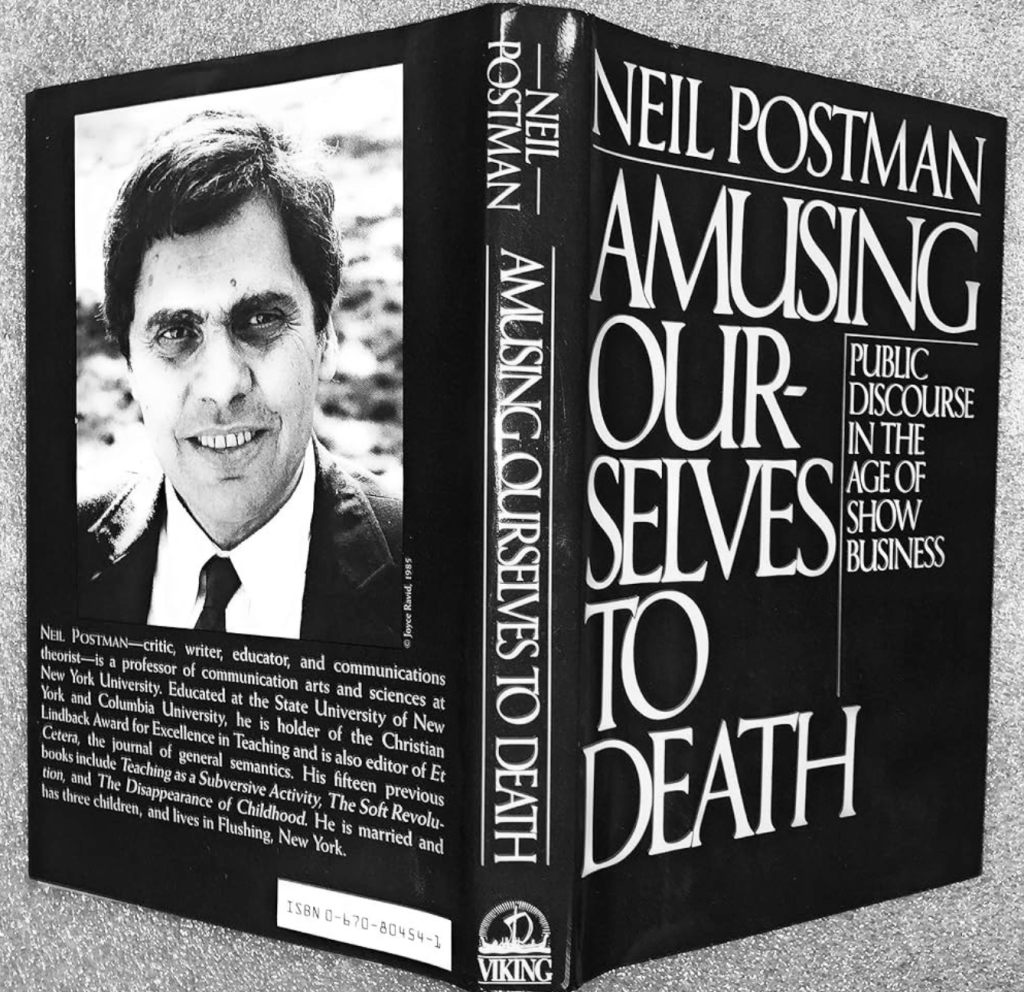

In the 1980s, the cultural critic Neil Postman built on the insights of the media guru, Marshall McLuhan, to emphasise how the visual character of news had changed the whole nature of public discourse. In various areas – politics, religion, education, the arts, business, the news media generally – reporting is image-centred so that it responds to the imperatives of entertainment and attention-seeking rather than the values of information or education.

This affects not only presentation but also content. It determines what is selected as worth saying, as well as how it is packaged and presented.

Entertainment naturally favours exaggeration – in fact, demands it. It calls for certain aspects of a story or report to be exaggerated – the historical significance of an event, the indispensable contribution of a central character – so as to find a place in the marketplace. In Postman’s words:

It is in the nature of the medium [of television] that it must

Amusing Ourselves to Death, 1985

suppress the content of ideas in order to accommodate the

requirements of visual interest; that is to say, to accommodate the values of show business.

A Place for exaggeration – opening a pathway to truth

Is there, then, any place for exaggeration in the conversations

of a culture?

Chesterton offered several insights into the value of exaggeration as a pathway to truth. He was, of course, himself accused of exaggeration, in his stories as well as in novels such as The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908). Many of the images in these works are weird and even hideous, as the literary scholar John C. Tibbetts has explored in The Dark Side of Chesterton: Gargoyles and Grotesques (2021). The images show Chesterton’s appreciation of exaggeration in trying to convey the nature of evil in life, and jolting us into a new consciousness of its power.

Chesterton knew that the presence of disturbing images – such as gargoyles on medieval cathedrals – in an otherwise beautiful setting spoke to the mixed realities of human life. They helped the ordinary human being to understand the mingling of agony and happiness in the human story – and the divine story of Christ – that the Christian vision captures.

“When a Christian is pleased,” wrote Chesterton, “he is (in the most exact sense) frightfully pleased; his pleasure is frightful. Christ prophesised the whole of Gothic architecture [when] he said: ‘If these were silent, the very stones would

cry out.”

The gargoyles fulfilled Christ’s prophecy, Chesterton thought:

the facades of the medieval cathedrals [were] thronged with shouting faces and open mouths.” The very stones cried out.

“The Eternal Revolution”, Orthodoxy, 1908

The Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges, was perhaps the first to probe the sombre insights in Chesterton’s writings that reflected the fullness of his spiritual understanding, keeping in balance his appreciation of joy.

Borges saw in Chesterton dark strains and hints of horror. Beneath the surface sparkle of wit and optimism, he thought, lurked a fear that the world

is a depraved and diabolic place. Chesterton, argued Borges, “restrained himself from being Edgar Allan Poe or Franz Kafka, but something in the make-up of his personality leaned towards the nightmarish, something secret, and blind, and central.” (“On Chesterton”, in Jorge Luis Borges, Other Inquisitions: 1937-1952 (1984))

Yet the point of Chesterton’s exaggerated plots or character developments in his fiction, and even his non-fiction, was not to distort the truth. He sought to enliven it – to reawaken our sense of reality that had become dulled by familiarity.

“Of one thing I am certain,” he wrote in 1903, “that the age needs, first and foremost to be startled; to be taught the nature of wonder.” (The Man Who Was Orthodox, 1963)

This need to be startled suggests, if not exaggeration, at least a striking novelty of vision and expression. At the very beginning of The Everlasting Man (1925), Chesterton made clear the approach he was taking to make clear the uniqueness of “the creature called man” and of “the man called Christ”:

We must invoke the most wild and soaring sort of imagination; the imagination that can see what is there.

Exaggeration and belief – our words become wild

In his widely acclaimed study of Charles Dickens, Chesterton linked exaggeration with the human need and capacity for belief. He thought that Dickens exaggerated a truth that was appreciated in the 19th century, in the aftermath of the French Revolution – the “sense of infinite opportunity and boisterous brotherhood” – but is not easily accepted in our time.

We now live in a period of history when we strive to control things – and to keep them within the bounds of human management. This can only undermine the capacity for a belief in higher realities, for we are fearful of being open to “the imagination that can see what is there.”

Chesterton offered a final insight into exaggeration when he wrote that “we are all exact and scientific on the subjects we do not care about. . . . But the moment we begin to believe a thing ourselves, that moment we begin easily to overstate it; and the moment our souls become serious, our words become a little wild.”