In the early 20th century, when the welfare state was being established, Chesterton provoked controversy by opposing compulsory workers’ insurance.

Britain’s National Insurance Act of 1911 and other measures, he believed, did not give workers the relief they needed. Rather, they were a new imposition of state power that would threaten individual and family freedom. This was a perversion of the popular will.

Chesterton opposed the new welfare state legislation, as Margaret Canovan argued in G.K. Chesterton: Radical Populist (1977), because he thought it was paternalistic and repressive. It took away the freedom of the poor and undermined personal initiative and family responsibility.

The socialist solution to poverty, Chesterton once said of George Bernard Shaw, was to distribute money among the poor. Chesterton thought that the need was “to distribute power”. In Canovan’s words, the social reformers added the insult of regimentation to the injury of exploitation.

Chesterton found himself against both the oppressors and the reformers. On the one hand, he opposed the entrenched upper class rich, who tolerated a society in which one-third of the population was perpetually on the verge of starvation. On the other hand, he took issue with the humanitarian idealists, whether they were Liberals (who introduced the welfare state) or Socialists (who believed the solution was to abolish private property rather than distribute it).

Welfare state – embedded but how sustainable?

The welfare state is now so taken for granted that it challenges the imagination to see the trap of dependency that so perturbed Chesterton.

In Australia, where the sad plight of the Indigenous people persists without solution, voices are occasionally raised questioning the value of welfare measures.

In 2011, for example, the Indigenous leader, Noel Pearson, lamented the damaging grip of dependency which the welfare state had imposed on his people (“Social policy begets social misery as the Western World fails the poor,” Weekend Australian, July 30-31, 2011). Most recently, his Cape York Partnership has called for a major revision of Indigenous politics and proposed “a post-welfare vision” for the most disadvantaged Australians regardless of race. (Paige Taylor, “Cape York Partnership’s radical plan to save all Australians from welfare trap and make education a legal right,” The Australian, November 18, 2025)

It may be that disquiet over a culture of dependency is destined to grow as doubts arise over the sustainability of the welfare state. When it was introduced – at first in Bismarck’s Germany in the 19th century, and later in Britain and worldwide – it was built on certain assumptions unstated at the time. Above all, it assumed a relatively stable society centred on the traditional

A Concerned Chesterton family.

But there were other, unrecognised assumptions. The first related to the demographic balance that prevailed – that the proportion of taxpayers to support a system of mass redistribution of wealth would greatly outnumber those receiving welfare benefits. An underlying assumption was that the fertility rate would continue at a high level, and that the family would remain intact to sustain this rate.

Another assumption was that those requiring welfare assistance would be confined to a relatively small minority of the population. It would be extended to only the most needy and vulnerable. There was no expectation that the balance of transfers – between those providing and those receiving – could be affected by such changes as a declining birth rate, a large intake of immigrants from overseas, or the breakdown of the family as a functioning social unit. Nor was it seen how corrupted it could be by political stratagems designed to buy votes in certain electorates through welfare handouts.

Welfare state and social expectations

Such developments have become unmistakable in Australia – and in the West. They now imperil the theoretical foundations of the welfare state. Our society is rapidly aging, and people are living longer. As birth rates drop, the percentage of aged pensioners changes in relation to the number of taxpayers – and thereby jeopardises the demographic balance that underpinned the welfare

state.

At the same time, a psychological barrier to any change may have developed at the popular level, so that dependency is accepted to the point where it saps the appetite for freedom. Chesterton was alive to this psychological factor as early as 1908: “When a great revolution is made, it is seldom the fulfilment of its own exact formula; but it is almost always in the image of its own impulse and feeling

for life.”

The “practical proposal” of the revolution might not be fulfilled, Chesterton thought, but its “ideal vision” would be. In other words, an entrenched welfare state shapes and seals social expectations. It becomes difficult to countenance

“turning back”.

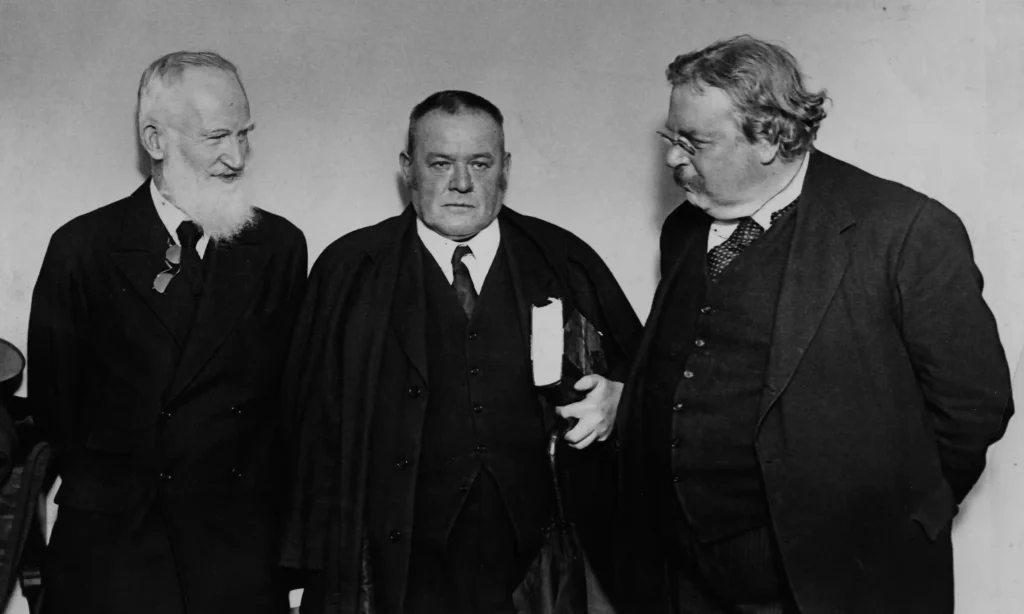

In company with Belloc, Chesterton feared that a servile attitude might have gained hold, after centuries of Big Business, with its relentless advertising promoting the conversion of wants into needs. And this was now reinforced by Big Government, with its pervasive provision of social services.

The force of Big Business had stimulated a culture of high – and rising – expectations that would be formidably hard to dampen, and the culture of Big Government heightened these expectations, creating a culture of entitlement.

Surrendering liberty for security

In the early writings of Distributists, there is a lurking fear that many people may have become so inured to the experience of security, of the sanctuary of dependence, that they would resolve the tension between security and liberty by giving up on liberty – and finding a certain satisfaction in being servile.

Chesterton loved the common people, but in The Outline of Sanity, he was troubled by the existence of a ‘servile disposition’. He described this condition as ‘a catastrophe of contentment’, and was troubled that it could envelop large numbers of people.

Belloc, in The Servile State (1912), recognised that the people at large retained ‘the instinct of ownership’, but he worried that our society had now reached a point where its modes of thought and habit were so permeated by collectivist assumptions and expectations that they would baulk at a wide distribution of ownership.

Why? Because it involved new demands of risk-taking and personal responsibility that a people conditioned by a collectivist culture and accustomed to the dependency of social provisions, would struggle with.

By contrast, private property implies the acceptance of personal responsibility. It is not an easy path to happiness, since freedom is a fraught condition – and a perpetually endangered gift.

Both Chesterton and Belloc nursed the fear that the psychology of a society conditioned by capitalism and socialism might induce people to give up on liberty for the sake of security and sufficiency – as occurred during the Covid era, when basic freedoms were surrendered, in response to a health crisis that was politically exploited in the name of safety.

Freedom is finally a spiritual need and condition, not just a social or political ambition. Can it be desired sufficiently by the people of the West, now swayed by social or political substitutes for religious faith, which have the effect of transferring power and responsibility to the state? Will it take a religious revival to reanimate the desire for freedom – inspiring personal initiative on the one hand, and buttressing personal responsibility on the other?