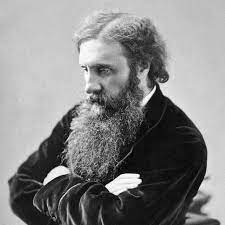

George MacDonald (1824-1905) was a Scottish Congregational minister who wrote books of fantasy – for both children and adults – as well as novels, poetry and sermons. Richard Egan, a frequent contributor to the pages of The Defendant, highlights MacDonald’s profound influence on both Chesterton and C.S. Lewis.

In his Introduction to George MacDonald and His Wife (1924) by MacDonald’s son, Greville, Chesterton writes:

“I for one can really testify to a book that has made a difference to my whole existence, which helped me to see things in a certain way from the start; a vision of things which even so real a revolution as a change of religious allegiance has substantially only crowned and confirmed. Of all the stories I have read, including even all the novels of the same novelist, it remains the most real, the most realistic, in the exact sense of the phrase the most like life. It is called The Princess and the Goblin, and is by George MacDonald, the man who is the subject of this book.”

In 1924, Chesterton chaired a celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of MacDonald’s birth.

In his autobiographical Surprised by Joy (1955), C.S. Lewis wrote of his first encounter with MacDonald’s work when as a sixteen-year-old he picked up a copy of MacDonald’s fanta- sy novel, Phantastes (1858). He later realised he had “crossed a great frontier”:

“That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptised: the rest of me, not unnaturally, took longer. I had not the faintest notion what I had let myself in for by buying Phantastes.”

Despite their genuine admiration for Macdonald, neither Chesterton nor Lewis endorsed Macdonald’s universalism – the doctrine that all human beings will ultimately be saved. As he expressed it in his sermon “The Consuming Fire”, Macdonald was absolutely convinced that it was a necessary consequence of the doctrine that God loves each of us that his infinite mercy will purify even the most hardened sinner.

This universalism is a persistent theme in his writings, including his novels, such as Robert Falconer (1868), which recounts a son tracking down his wayward father, and urging him to repent. “You will have to repent some day, I do believe— if not now under the sunshine of heaven, then in the torture of” hell.

In his Autobiography (1936), Chesterton comments on Macdonald’s universalism, referring to what he calls “the glamorous mysticism of George Macdonald”:

“It was full and substantial faith in the Fatherhood of God, and little could be said against it, even in theological theory, except that it rather ignored the free-will of man. Its Universalism was a sort of optimistic Calvinism.”

In Lewis’ theological dream fantasy novel The Great Divorce, Macdonald takes the role of Dante’s Virgil in guiding the narrator through purgatory/hell. In this dialogue between the narrator and Macdonald, it could be said that Lewis is attempting to reconcile Macdonald’s universalism with the orthodox position that eternal damnation is a real possibility, precisely because of the reality of human freedom.

“In your own books, Sir,” said I, “you were a Universalist. You talked as if all men would be saved. And St. Paul too.”

“Ye can know nothing of the end of all things, or nothing expressible in those terms. . .

“The choice of ways is before you. Neither is closed. Any man may choose eternal death. Those who choose it will have it. But if ye are trying to leap on into eternity, if ye are trying to see the final state of all things as it will be (for so ye must speak) when there are no more possibilities left but only the Real, then ye ask what cannot be answered to mortal ears.

“Time is the very lens through which ye see – small and clear, as men see through the wrong end of a telescope – something that would otherwise be too big for ye to see at all. That thing is freedom: the gift whereby ye most resemble your Maker and are yourselves parts of eternal reality.”

Thankfully it is not necessary to accept all an author’s beliefs to benefit from reading their works – otherwise we may have very bare bookshelves indeed. In the early 1970s, when I first read everything of CS Lewis’s that I could get my hands on, and came across references to George Macdonald (and Charles Williams), it was almost impossible to find their books. Later I read Princess and the Goblin (1872) and At the Back of the North Wind (1871) to my children.

Thanks to Librivox and Project Gutenberg, I have now listened to or read on my phone several of Macdonald’s novels. For those who haven’t yet dabbled in Macdonald, I encourage you to do so.