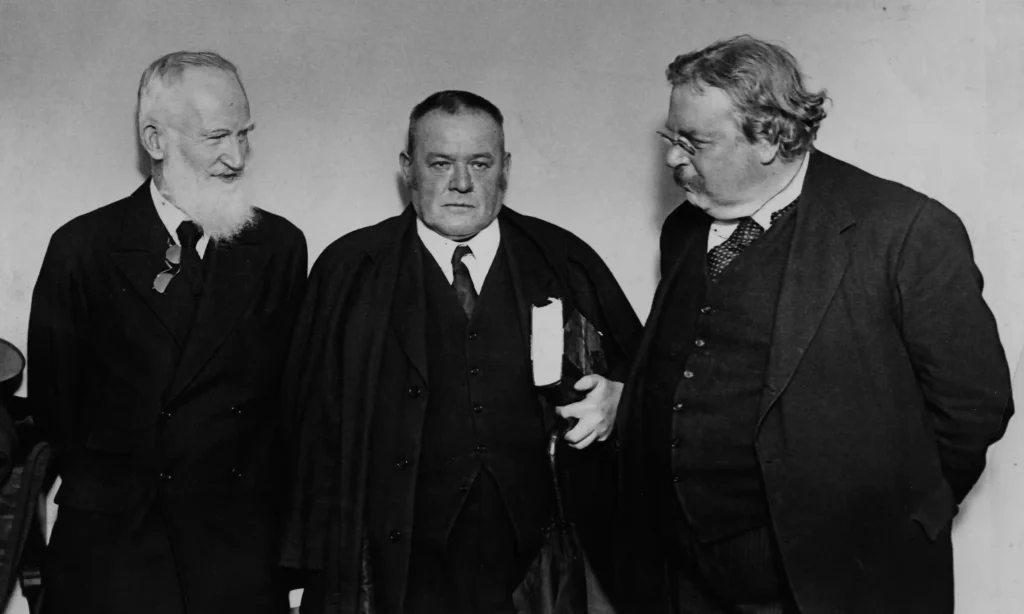

George Bernard Shaw and a Benedictine Nun

The playwright and social critic, George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), was a long-time admirer of Chesterton, whom he described as “a colossal genius”. Their friendship transcended their disagreements on virtually every subject, particularly religious faith, as Shaw was a professed atheist.

Yet a little-known fact about Shaw, which brings a certain nuance to his presumed disbelief in God, is that he had an even less likely friendship. This was with a cloistered nun, Dame Laurentia McLachlan (1866-1953), who was Abbess of the Benedictine Abbey of Stanbrook in England. They met through a mutual friend after Dame Laurentia had expressed admiration of Shaw’s play, St Joan (1923). Following a visit which Shaw and his wife made to Stanbrook, Dame Laurentia wrote:

“It seems that the life here, and therefore the Church does attract him. God give me grace to help this poor wanderer …” Later Shaw sent her a copy of St. Joan inscribed: “To Sister Laurentia from Brother Bernard.” The friendship flourished, mainly by correspondence that addressed issues of Christianity and faith. Excerpts from these letters proved of wider interest. They were published in book, In a Great Tradition (1956). They also appeared in magazines in England and America at the time. Later they formed the basis of a stage play by Hugh Whitemore, The Best of Friends (1988).

Religious longings – and the freedom of the enclosed life

The letters shed a telling light on Shaw’s religious needs – and his understanding of the value of a cloistered life.

“When we are next touring in your neighbourhood,” he wrote, “I shall again shake your bars and look longingly at the freedom on the other side of them.’

From the Holy Land he brought back two pebbles, “one to be thrown blindfold among the others in Stanbrook garden so that there may always be a stone from Bethlehem there, though nobody will know which it is and be tempted to steal it, and the other for your own self.”

The second stone he had mounted on a silver model of a mediaeval reliquary, surmounted by a figure of the child Jesus. When it was suggested that it bear some kind of inscription, he wrote: “Why can it not be a secret between us and Our Lady and the little boy? What the devil – saving your cloth – could we put on it? … Our fingerprints are on it, and Heaven knows whose footprints may be on the stone. Isn’t that enough?”

Again and again Shaw asked for the nuns’ prayers: “Nobody can tell what influence these prayers may have. If the ether is full of these impulses of goodwill to me so much the better for me: it would be shockingly unscientific to doubt it. So let the Sisters give me all the prayers they can spare; and don’t forget me in yours.”

Shaw’s sardonic allegory, The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (1932), tested his friendship with Dame Laurentia, though he insisted that it was directly inspired by God. He wrote on the flyleaf of the proof sheets he sent her: “An Inspiration which came in response to the prayers of the nuns of Stanbrook Abbey and in particular to the prayers of his dear Sister Laurentia for Bernard Shaw.”

But they argued over it by mail. “You are the most unreasonable woman I ever knew …”. wrote Shaw in frustration. “You think you are a better Catholic than I, but my view of the Bible is the view of the Fathers of the Church; and yours is that of a Belfast Protestant to whom the Bible is a fetish. … But you must go on praying for me, however surprising the results may be.”

Towards the close of his long life, the elderly Shaw would pause happily on his birthday, among the scrap baskets full of congratulations, to thank his cloistered friend for her good wishes:

“If I try to sneak into paradise behind you they will be too glad to see you to notice me,” he wrote once.

His 94th and last birthday marked the end of these exchanges: “God must be tired of all these prayers for this fellow Shaw whom He doesn’t half like. He has promised His servant Laurentia that He will do His best for him, and we had better leave it at that.”