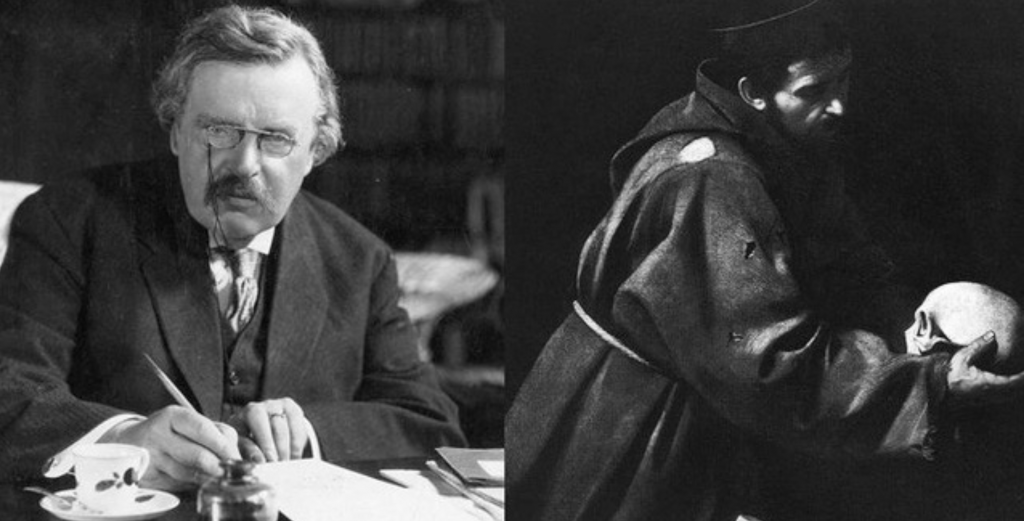

As Holy Week in the Christian calendar approaches, we become conscious once again of the death of Christ. Our thoughts may even take a counter-cultural turn and confront the reality of death itself. Dale Ahlquist, President of The Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton (formerly the American Chesterton Society), offered a timely reflection on this subject in Gilbert Magazine (July-August 2019). The article is reprinted with his kind permission.

We used to keep death close, even stare it in the face: the skull on the desk beside the book, the graveyard right next to the church, crypts under the floors where we knelt.

We kept death close to remind us that we must die. There was a fear of death, but it was a very healthy fear. It made us live better lives. By watching the dead we watched ourselves. By contemplating the mystery of the next life, we took an active interest in the mystery of this life.

“For some strange reason,” says G.K. Chesterton, “man must always plant his fruit trees in a graveyard. Man can only find life among the dead.”

But he saw us losing our fruitful fear of the morbid. Now we have hidden away our cemeteries, and, what’s more, as Chesterton predicted, we have returned to the pagan habit of cremation. We have scattered our ashes, and the wind has blown away the memory of the dead. We have stopped thinking about the brevity of this life, and in the process have also stopped thinking about the breadth of eternity.

And a strange loss of balance has occurred, even a loss of sanity, which is what happens when there is a loss of mental and spiritual balance.

We used to fear death. Now we fear life instead. We used to fear abnormal things, like sexual perversion and slaughtering babies in the womb. Now we fear normal things, like the weather.

We no longer throw the meaningful shovelful of dirt on the coffin because now the dirt has become more sacred than the dead. We mutilate our bodies in the most unnatural ways, yet we wring our hands about using too much air or too much water or too much bread. We do not worry that we are destroying our individual homes with adultery and divorce and contraception and abortion, but we are obsessively worried that we are destroying our shared home the earth by turning on lights, growing corn, eating meat, driving cars.

Cowering before the climate

We have grown afraid of the primal and primary tools of civilization—fire and farming and the wheel—because they might interfere with the earth and sky.

We are afraid of the normal, human things because we have forgotten the dead. We don’t read them, we don’t remember them, and we have forgotten who we are. We have forgotten that we are civilized.

Civilization has always interfered with the forest. As soon as the plow breaks the soil, man declares his supremacy over nature. But now we cower before the climate.

Chesterton says, we can predict the stars, but we cannot predict the clouds. Amazing how he continues to be right about that one. In spite of our sophisticated meteorological equipment, we still can’t predict the clouds. We still cannot infallibly forecast sunshine or rain tomorrow.

That of course won’t stop us from checking the weather report. It is harmless when planning for a picnic. But it is a grave matter (ha!) when we have chosen to follow into the wilderness the most consistently wrong prophet in all of history: the weatherman.

Here is Chesterton talking about the weather: “On the bright blue day my spirits go slightly down; there seems something pitiless about perfect weather. On the clear cool day, my spirits are normal. In the fog, my spirits go up; it feels like the end of the world, or better still, a detective end of the world. He is not the first prophet to make this prediction.

Chesterton says, “It is very natural but rather misleading, for supposing that this epoch must be the end of the world because it will be the end of us.” And yet, one of these times it will really be the end of the world, even if a wobbly prophet says so.

For the Christian, the final revelation is a good thing, the apocalypse, the unveiling, the solution to the mystery, the explanation not only of all things, but of that most mysterious thing: ourselves.

Chesterton cannot help but anticipate what, in truth, we have all been waiting for: “No men will ever know each other till the end of the world.”

But here’s a thought. What if the climate change alarmists are absolutely right? And what if we do not heed their warnings? What if we proceed on this path to destruction? What if there is nothing they can do to stop us? What if we are all going to burn up, if not quickly, then slowly and surely? Will those who will have lost their hope about saving the earth have any concern to save their souls? Will they consider Jonah and Nahum and Nineveh? Will anyone ever repent?

Instead of the thundering hoof beats of the Four Horsemen story.” of the Apocalypse, perhaps the Judge will come riding in

Paradoxical and profound as expected. Good weather brings him down, bad weather lifts him up. And he sees the end of the world in the weather. He also sees a mystery. The fog is full of riddles. But the finality at a certain point is certain. Now we have the weatherman telling us it’s theat a plodding pace, maybe even on a donkey, but without fanfare, without trumpets.

Perhaps he will quietly dismount and silently switch off the lights. The heat will be eternal, but the stars will all go out. Just a thought.