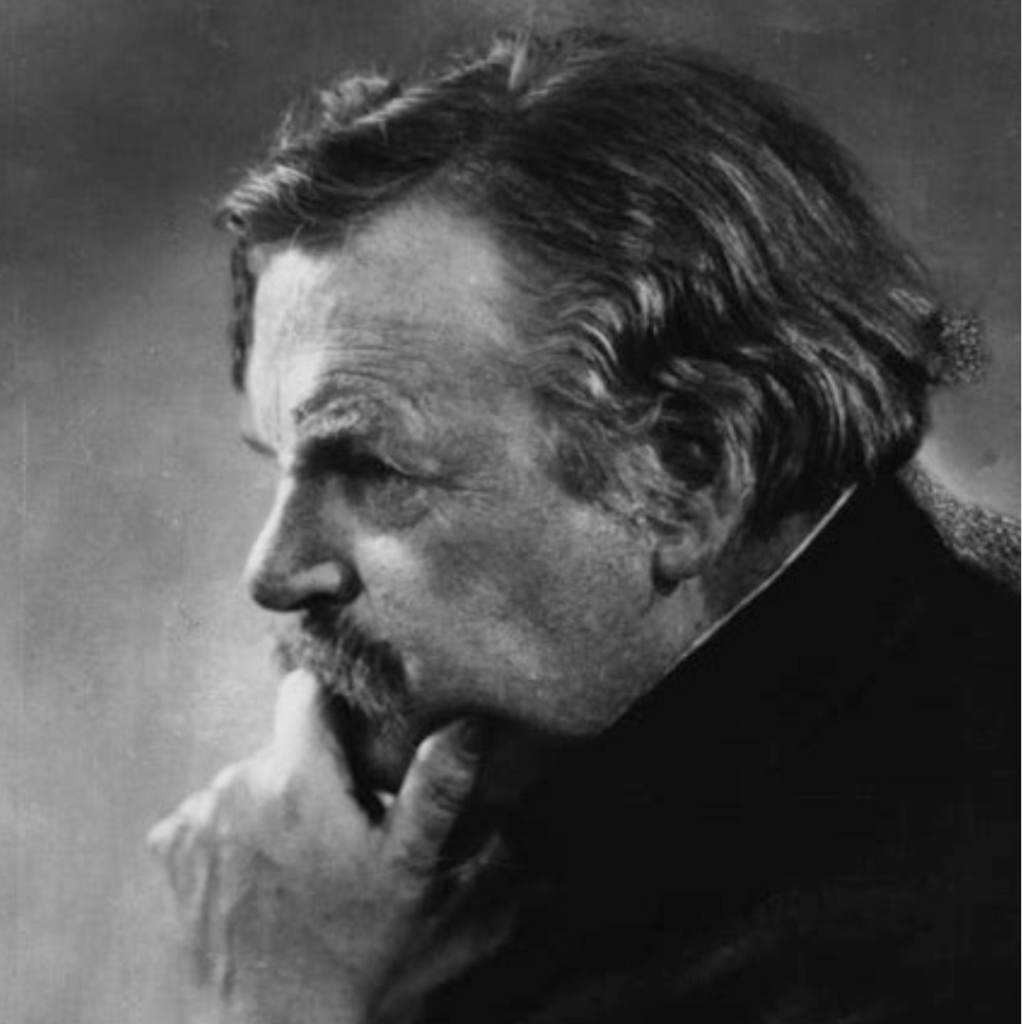

More than a century ago, Chesterton made an arresting prediction – that the slide into barbarism would come, not from the abandonment of civilisation, but from over- civilisation.

He observed that:

the fads of the cultured grow every day more pleasingly

“Taboos and Prohibitions,” Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton, Vol.28, Illustrated London News, 1908-1910. Ignatius Press, 1987

identical with the habits of the barbarian… Over-civilisation and barbarism are within an inch of each other. And a mark of both is the power of medicine- men.

Chesterton made these remarks in 1909. What would he have made of the surging legalisation of abortion and euthanasia in the contemporary West? These acts are now promoted, not as a regrettable necessity in hard circumstances, but more and more as indisputable human rights, which should be constitutionally guaranteed.

They are only possible, finally, through the professional power and compromising participation of certain “medicine-men”.

No doubt Chesterton would have seen that his prophecy is being fulfilled – to a horrifying extent. The “fads of the cultured” – the wealthy and professional elites – are coming more and more to resemble “the habits of the barbarian”, as our culture resorts increasingly to deliberate killing, at the beginning and at the end of life.

The myth of inevitable progress

An historically powerful impulse lurks behind Chesterton’s insight into the link

between over-civilisation and barbarism – namely, the yearning for inevitable

progress.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was in the West an eruption of utopian writing, in both fiction and non-fiction. Science was envisioned as the pathway to irresistible progress – and the assured hope of the future.

H.G. Wells, a popular contemporary of Chesterton, was one of the fathers of science fiction. His dream was inspired, as one biographer noted, by “science as its god, evolution its history, and nature – including man – its congregation.” (Lovat Dickson, H.G. Wells: His Turbulent Life and Times, 1969)

Wells’ early expressions of exuberant hope appeared in such books as Mankind in the Making (1903) and A Modern Utopia (1905). While the destructive horrors of the First World War – such as poisonous gases and artillery bombardments – shook this dream, it did not destroy it. The myth of progress

continued – as is clear from the ease with which one side of politics, the left, is still commonly called “the progressive left”.

In his closing years – he died in 1946 – Wells lapsed into despair, but of a kind that is peculiarly true of our own time. He embraced a different, ‘over-civilised’ hope.

In his last book, Mind at the End of its Tether (1945), he confessed that he had misread human nature, and that he had “no compelling argument to convince the reader that he should not be cruel or mean or cowardly.” His loss of faith in humanity led him to search for a new hope – and conceive of an entirely new species which would be perfect, and would replace the flawed human being in whom he had invested his trust, but who had hugely disappointed him.

But as Chesterton once commented about utopianism:

Hope for the superman is another name for despair of

Heretics, 1905

man.” It is as if the only counter to the onset of despair

is to conjure up even more extravagant earthly hopes.

Chesterton’s hope, by contrast, was in man as he is, not as he is imagined to be – that is, in the world of reality, not in the dreams of fantasy. As he once argued, what is most valuable and lovable in our eyes (and, he implied, in God’s eyes) “is man – the old beer-drinking, creed-making, fighting, failing, sensual, respectable man.

And he went on, in one of his most majestic passages of prose:

The things that have been founded on the fancy of the

Superman have died with the dying civilizations which alone have given them birth. When Christ at a symbolic moment was establishing His great society, He chose for its corner-stone neither the brilliant Paul nor the mystic John, but a shuffler, a snob, a coward – in a word, a man. And upon this rock He has built His Church, and the gates of Hell have not prevailed against it.All the empires and the kingdoms have failed, because of

Heretics, 1905

this inherent and continual weakness, that they were founded by strong men and upon strong men. But this one thing, the historic Christian Church, was founded on a weak man, and for that reason it is indestructible. For no chain is stronger than its weakest link.

False gods and false devils

A second Chesterton prophecy in his 1909 essay was that the essence of

barbarism was idolatry. “Idolatry is committed,” he wrote, “not merely by

setting up false gods, but also by setting up false devils.”

Chesterton singled out the earthly fears that can readily take grip of people, such as the fear of “war or alcohol or economic law,” when he thought there were far greater reasons for fear: “they should be afraid of spiritual corruption

and cowardice.”

The setting up of false gods inevitably calls for false devils. Devils tend to induce a pervasive sense of fear, which, in turn, serves to reinforce the worship of false gods.

Chesterton could hardly have foreseen how easily our culture would come to be gripped by fear and easily “offended”, and how strongly legislative measures and policing practices would be enforced to prevent people being “offended”. If the god being worshipped is imagined, it can only be protected from scrutiny by imagined devils.

Our own age abounds in false devils, which are bound to incite fear. A culture that falls for illusions inevitably becomes a fearful culture.

Probably the most insistent of today’s fears, especially for the young, is climate change, but others relate to the atmosphere generated by the rise of ‘wokeism’ and the playing out of identity politics, mainly of race and gender. Curiously they rarely touch the category of class, which was such a dominant category of Marxist discrimination. This could be because the woke elites are actually among the wealthiest in society, and assuage their guilt over such privilege by defending, at a distance, the plight of the poor.

Chesterton’s prophecy is tragically coming to pass. The “fads of the cultured” are now becoming identical with “the habits of the barbarian”.