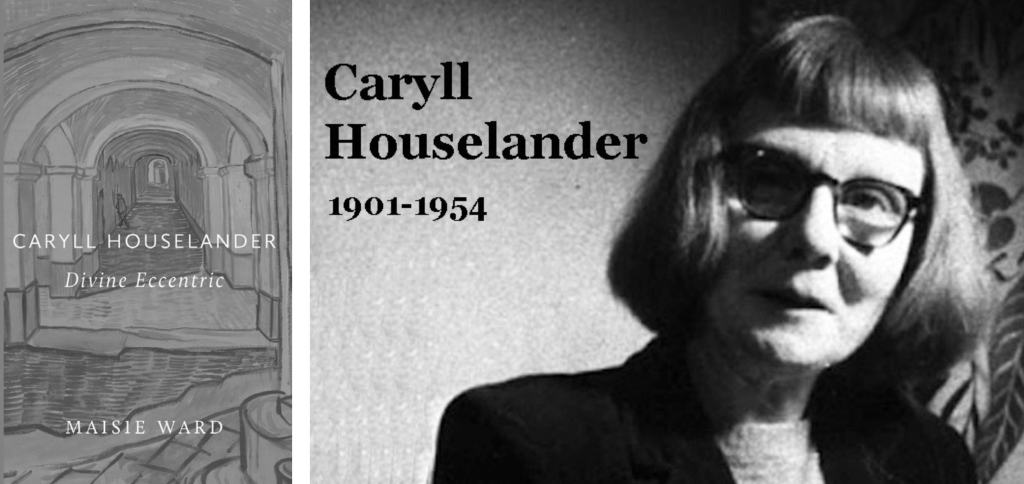

Francis Phillips, a frequently published English writer and a valued contributor to The Defendant, captures the distinctive qualities and insights of Caryll Houselander, an English author and artist (1901-1954). This article first appeared in April 2022 in Mercatornet, and is reprinted with the kind permission of its editor, Michael Cook, as well of Francis herself.

Shakespeare writes in Julius Caesar, “The evil that men do lives after them, the good is oft interred with their bones.” Sometimes excellent writers also get buried after their death; their books fall from public interest. Decades later they are rediscovered for a new readership.

This literary cycle could be applied to the life and writings of the English wood carver and mystic, Caryll Houselander, widely read in the pre- and post-war period who then faded from view.

Cluny Publications now brings her to the attention of modern readers in a republication of Maisie Ward’s 1962 biographer of her, Caryll Houselander: Divine Eccentric.

The description “divine eccentric”, bestowed on her by a psychologist friend, is a concise summary of her unique personality. Houselander was certainly touched by the divine, transcending the loneliness of her youth. A gifted artist and writer, she applied the spiritual insights she had learnt from her own sufferings to her books and to consoling her many friends, followers and readers in their own struggles.

Indeed, although often in poor health she exhausted herself in being available to others; she could not shut the door on anyone. In her company they felt enveloped by her understanding and compassion. Despite constant fatigue and the deadlines for her writing and carving commissions, Caryll was enormously generous with the time she gave to those who demanded it of her.

Her rule was: “To choose always the thing to do into which she could put the most love.”

Her oft-repeated insight was that “We must learn to see Christ in everyone”, to which she gave a renewed urgency in the times in which she lived, particularly during World War II. She wrote in her Journal, “Some people cling to what is past; some, the fewer and braver, face the future; but to live harmoniously in the present is an almost superhuman task”. This was the task she set herself.

A fresh vision – seeing everything for the first time

This War is the Passion, the title of her first book to be widely read, published by the Catholic publishers Sheed and Ward, was a collection of her articles written about the War. Monsignor Ronald Knox, a convert like Caryll, made the acute observation, “She seemed to see everything for the first time.” It was this immediacy and freshness of her spiritual writing that attracted readers, struck by the clarity and simplicity of her prose style and her unaffected originality.

What also drew readers to Caryll was her admission of her own weaknesses. In her autobiography she tells the story not “of her life but of what drove her out of the Church and of how she returned to it.”

She writes candidly of her love affair with the spy Sidney Reilly, who had lived in Russia before the Revolution and who eventually disappeared in the Terror. Her oddity is also implicit to this story: Caryll was instinctively at odds with conventional piety. With her bright red hair, thick glasses, and her mask-like face, on which she applied layers of white cream which made her look like a clown, most people would have found her disconcerting.

“Eccentric” barely does justice to Caryll’s style of living, in which she crammed little sleep, less food, much merriment, fun and entertaining, cigarettes, strong language, her carving and writing, an intense devotional life and a wide range of devoted friends.

Unsparing honesty – unswerving seriousness

Her unsparing honesty about herself is endearing. A journal entry for March 6th 1929 reads, “After all these Holy Communions, Masses, Confessions, books, rules, resolutions – nothing is done. No, God forgive me, His grace works silently, secretly; in the hour of trial, I shall know that it is so – I need to trust. But alas I know this: I am as unkind as before, my tongue as violent, my mind as melancholy, my will more weak, my fervour died out, my self-indulgence grown as I could never have imagined, my spirit of prayer fading…”

There is some over-scrupulosity here and, as Maisie Ward comments, “’Self-indulgence’ seems always to mean smoking. Caryll resolved to fine herself a penny for every cigarette in excess of the allotted daily ten.”

Beneath this portrait of “a wit, a conversationalist…with a contagious sense of fun, an altogether delightful companion”, lay a person of unswerving seriousness, who knew her vocation to be “to bring to men the truth that Christ is in men; and it involved bringing alive in them the great truths about Him and about their own souls.”

The core teaching of Christianity, which she wrote in a letter to a friend just before the Blitz, in October 1940, is simple: “The real thing…depends not on what school of thought one grew up in, or what creed one believes in, but on one’s capacity for love and for humility.”

Again: “The healing of mankind begins whenever any man ceases to resist the love of God”.

As someone who spent much of her later life befriending patients in a mental asylum, Caryll brought her own unconventional life experiences, along with her gifts and insights, into her approach.

She was a natural mystic, clairvoyant in her grasp of the supernatural reality beneath the surface of life, demonstrated by her account in her autobiography of three extraordinary interior “visions” she had as a young woman.

The last of these occurred on a crowded tube train in London when “she saw Christ” in all the people around her, “living in them, dying in them, rejoicing in them and sorrowing in them”. In a passage of stark spiritual perception, Caryll

concludes this mystical “vision”:

I saw too the reverence that everyone must have for a sinner; instead of condoning his sin, which is in reality his utmost sorrow, one must comfort Christ who is suffering in him. And this reverence must be paid even to those sinners whose souls seem to be dead, because it is Christ, who is the life of the soul, who is dead in them; they are His tombs, and Christ in the tomb is potentially the risen Christ.

Maisie Ward also quotes from some of the innumerable letters that Caryll sent to friends and other correspondents. She had an instinctive understanding of human psychology and was usually correct in her diagnosis of where her correspondents’ problems lay.

Her book Guilt explores the psychological suffering experienced by those who cannot face their sinfulness and who hide behind fashionable therapies which

offer [man] an escape from the responsibility of being human, for the soulless man is not a human being.” She was firmly convinced that anyone can become a saint, including neurotics among whom she counted herself: “The one essential for sanctity is the capacity to love.

Readers have sometimes first encountered Caryll through her book on Our Lady, The Reed of God (1944), which has made them curious to read more of this unclassifiable author. Other titles include The Flowering Tree, a collection of her prose-poems, which she called her “rhythms”.

Sometimes her imaginative response to a dilemma was much larger than its possible execution, as her more practical friends pointed out to her. She always gave herself wholeheartedly to whoever she was with and whatever activity she was engaged upon; despite her austerities, her energy was formidable.

After being recommended her autobiography years ago, I discovered that she was buried in a churchyard only a few miles from where I live in Buckinghamshire.

Her long-time friend, Iris Wyndham, had bought a cottage in the area where Caryll used to work in a studio in the garden when she was well enough to do so. For this garden she had carved a tender Madonna and Child in wood, still in the branches of an apple tree where it was first placed.

Since my discovery of this link, every so often I drive over and tend to her grave which would otherwise be neglected. Someone has to do this. Such an indomitable spirit, touched by a quirky, unique and generous genius, should not be forgotten.