Last September, a Chesterton essay written in the 1930s, which had long remained hidden in library archives in England and America, was finally published.

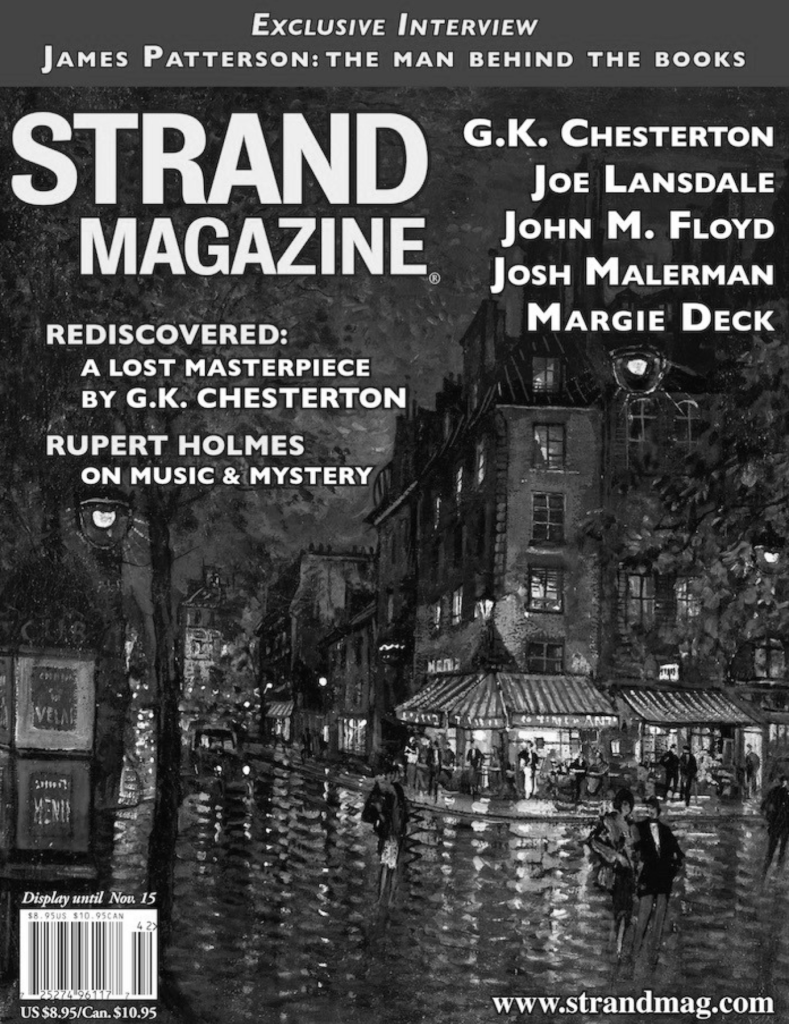

The essay, “The Historical Detective Story”, was printed in Strand Magazine, and reported on by Martin Pengelly in The Guardian and Hillel Italie of Associated Press (20 September 2024).

Chesterton argued that “the detective tale is almost the only decently moral tale that is still being told” because “it is only in blood and thunder stories that there is anything so Christian as blood crying out for justice to the thunder of the judgment.”

But, he thought, writers of detective fiction should search for fresh sources, to escape what even a century ago was the cliché of the country house murder. This would provide “some new liberties, as well as some new limitations.”

Chesterton proposed that an unsolved murder from the past might form the inspiration of a new novel that would explore how that person had met their death. Might one possibility be the mysterious death of a 17th century London magistrate, Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey? Could this be the ultimate historical whodunit?

“I suggest,” Chesterton wrote, “that we try to do a little more with what may be called the historical detective story. Godfrey was found in a ditch in Hyde Park, if I remember right, with the marks of throttling by a rope, but also with his own sword thrust through his body.

“Now that,” wrote the creator of Father Brown, “is a model complication, or contradiction, for a detective to resolve.”

As it happened, no one picked up on the idea – presumably because the essay was never published and no evidence has been found of any response to it.

In a brief foreword to its publication in Strand Magazine, Dale Ahlquist described the Chesterton essay’s long journey to publication as its own kind of mystery.

One copy was found in the rare books division of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana (USA), while another was included among Chesterton’s papers that are now in the British Library in London. As Dale pondered, given Chesterton’s vast output not only of books but of essays that number at least 8,000, scholars may well have presumed it had already been published.

Detection Club – and an essay calling for a detective

The essay that has now appeared is linked to Chesterton’s membership of the Detection Club. Dale called the Club a “secret society of mystery writers . . . who met regularly in a private room at L’Escargot”, a restaurant in Soho in central London. They would exchange ideas and even work on books together.

Chesterton was elected as its first President, and founding members included Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Ronald Knox, and A.A. Milne. More recent members have included John le Carré, Ruth Rendell, and P.D. James.

The Club planned an annual magazine, for which Chesterton’s essay may have been intended, but the publication never materialised.

The copy of the essay in the British Library, presumably the archival copy, was found with a note from Chesterton’s long-serving secretary, Dorothy Collins. It said that the essay had been sent on to the Detective Club Magazine. But there was no magazine of that precise name. She probably meant ‘Detection Club’.

Whoever received that initial copy may have held on to it until, at some stage, it found its way – perhaps via a private collector – to the University of Notre Dame.

“A real detective,” as Dale concludes, “would track all this down.”

Chesterton himself might have been wryly amused by this episode – that he should have written an essay which would mysteriously remain unpublished in his lifetime, and that it should have been on, of all subjects, “the Historical Detective Story”!